This is the story of, perhaps, an unspectacular man, a soldier who experienced both garrison posting and war, volunteering and public service. It is not an altogether new story, but a life that has been told in part previously though never in full. In the October-December 1980 edition of the MHSA journal Sabretache there was a paper by Robert Williams based on an account in a British newspaper, the Wolver Hampton Chronicle of 4 February 1857. The article recounted an incident, no doubt drawn from a contemporary Australian newspaper, which took place at Melbourne’s Prince’s Bridge barracks during the garrison occupancy of Her Majesty’s 40th Regiment of Foot. Prince’s Bridge barracks are believed to have been a temporary barracks on the eastern side of St Kilda Road pending the construction of Victoria Barracks on the western side.

In brief, an Ensign of the regiment went on a rampage with a pistol, murdering the Regimental Medical Officer who was recuperating from an accidental fall, then wounded two of his brother officers before taking his own life. One of the wounded officers was the subject of this paper, Ensign deNeufville Lucas*

*Despite most written instances of the name being spelled using the upper case ‘De’, the author has followed the few examples of his signature i.e. ‘deNeufville’.

De Neufville Lucas attested into the 40th Foot as Ensign (without purchase) on 17 August 1855 at the age of 22½ years. Just a few months later he was posted to join his regiment in Australia, arriving in Melbourne aboard the Epsom in July 1856 in the company of at least three of his brother officers, two of whom (Veith and Pennefather) became involved in the incident referred to here.

Detailed accounts of the barracks rampage were recorded not only in the Melbourne newspapers but also in Sydney, Adelaide, Hobart, Perth and of course subsequently in the Wolver Hampton Chronicle. The incident was reported thus (Ensign Veith is misreported as Keith):

His Excellency the Governor held the usual half-yearly inspection of the troops in garrison yesterday. At the Princes Bridge Barracks, when the 40th Regiment was paraded, it went through various evolutions. The inspections being over the officers retired to their quarters, and Ensign Pennefather and others engaged in familiar and friendly conversations. Shortly afterwards, between 12 and 1 o’clock, Ensign Pennefather rushed out of his room with a six barreled revolver in his hand, and meeting, just as he got outside of the house, Ensign Keith, he presented the pistol and fired at him. The bullet passed through Ensign Keith’s cheek and came out at the back of his neck. At this time Dr. McCauley was seated in an arm-chair on the grass in front of his quarters, reading. In consequence of an accident he met with since by falling from the gallery upon the vestibule of the Theatre Royal, the doctor was an invalid, and his crutch lay at his side. After firing at Ensign Keith, Pennefather ran to where Dr McCauley was sitting, and placing the pistol on the doctor’s mouth, he fired, and the bullet passed out at the back of his neck. Pennefather then looked round as if anxious to find someone else to shoot, when Ensign Lucas ran forward to wrest the pistol from him. On seeing him approach Pennefather shot him in the jaw. With a maniacal ‘Ha Ha’ the wretched man then placed the pistol at his own head and fired, the bullet entering the right temple. Such, as near as we can learn, are the brief but shocking incidents of this disastrous affair.

Apparently Dr McCauley died immediately, while Ensign Lucas was severely wounded and Keith dangerously so. Ensign Pennefather lingered for about nine hours before he died while Lucas recovered from his ‘severe’ injury, although the bullet remained embedded in his tongue for the next eighteen years. The inquest on the deceased officers took place on Thursday 23 October in an apartment of the officer’s quarters, the subsequent finding of the jury being ‘That the deceased Vere Fitzmaurice Pennefather, had died from injuries inflicted by his own hand, whilst in a temporary state of insanity’. There are some newspaper observations and correspondence questioning whether the inquest had any justification or expertise for declaring Pennefather insane or deranged but nothing of substance resulted. The burial of the officers was quite an occasion with practically the whole of the regiment (less those sick or on duty), the band, the firing party and even the Governor’s carriage following the bodies. Pennefather and Doctor McCauley were, somewhat bizarrely, buried head to head, sharing a headstone between them in the Melbourne cemetery.

Despite being severely wounded, Ensign Vieth recovered and went on to further service. It was not until the Monday following the incident that Ensign Lucas is reported as ‘…going on favourably, and is able to speak’. Lucas’ health continued to improve and he remained in the service of the 40th. He was subsequently transferred to Adelaide with No.3 Company, arriving on 13 April 1858 when it relieved the detachment of the 12th Regiment bound for Melbourne, thence Sydney to replace the 77th Foot posted to India. Lucas was promoted to Lieutenant (without purchase) on 28 October 1858.

Although a serving garrison officer, deNeufville Lucas was able to secure in 1861 a Staff appointment to the Volunteer Military Force as Sub-Instructor (in Drill and/or Musketry), still maintaining his regular army rank. This was to lead to a fairly long though interrupted involvement with the Volunteer forces in South Australia. His appointment put Lucas frequently in the public eye. He was seen at many functions involving the volunteers, such as rifle matches, parades and reviews, levees and similar occasions, as well as travelling to country districts around the colony to classify and drill volunteer companies located outside the greater metropolitan area.

It was not long before Lt. Lucas was called into active service. Parts of the 40th had been called in from Melbourne and Hobart for duties in New Zealand during April 1860 due to Maori unrest and over the next two years or so they saw considerable action. By 1863 the continuing struggles led to the remainder of the troops stationed in Australia to be largely withdrawn and transferred to New Zealand as reinforcements. Between September and November 1863 all detachments of the 40th Regiment, with the exception of a few men in Tasmania and Victoria, were withdrawn and concentrated in New Zealand.

Lucas arrived in New Zealand on 5 November. It is not clear just where Lucas served in New Zealand, but his service entitled him to, and he was awarded, the New Zealand medal. His medal though had the undated reverse because he had resigned from the army before the medals were issued; and this was not until 1869.

Lucas returned to Adelaide in the first half of 1866. On Lucas’ return he picked up an appointment as Provincial Aide de Camp to Governor Sir Dominic Daly, gazetted on 24 May 1866 then, five months later, Lt. Lucas retired from the army by sale of his commission on 30 October 1866. However, he maintained his situation as ADC to the Governor until 2 March 1868. During this period as ADC to the Governor Lucas again was regularly in the public eye and frequently mentioned in the press, performing many duties from simply supporting the Governor on formal occasions to delivering personal messages or gifts on behalf of His Excellency. Other duties would have included attendances at formal Government House levees, Vice-Regal theatre attendances, parades and picnics.

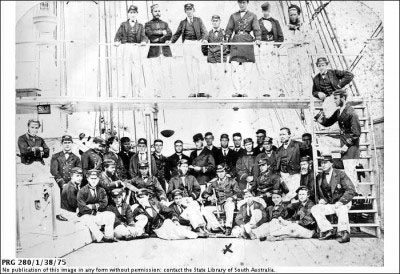

He was ADC to one Governor (Sir Dominic Daly) for nearly two years and one Acting Governor (Colonel Hamley, 50th Regiment) for about 8 days after the death of Sir Dominic. Lucas was closely connected with duties related to the visit of HRH the Duke of Edinburgh in 1867; during the visit of Prince Alfred Lucas acted as his Aide de Camp. Whilst serving as Daly’s ADC Lucas was also appointed an Honorary Major on the Staff of the Volunteer Military Forces, effective from 22 July 1867. No photograph of Lucas has been located but there is one photograph of the visit of Prince Alfred in 1867 which shows, aboard the Galatea and among all the naval personnel we see one military officer; this is possibly Major Lucas in his role as the ‘borrowed’ ADC to the Duke.

Between 1870 and 1873 Lucas held the joint posts of Assistant Staff Officer (with the rank of Major), Enrolling Officer (that is, for enrolling volunteers) and also Storekeeper to the VMF, then in 1874 became Government Storekeeper on the VMF Staff (possibly simply a bureaucratic re-naming of the duties he had previously been performing) and this was the post he held until 1880. His formal relationship with the Volunteer movement appears to have finished at this point, though he continued working in the Public Service, taking on the position of Records Clerk in the South Australian Railways based at Adelaide Railway Station between 1880 and 1891. He was then transferred from Adelaide to the Islington Railway Workshops a few miles north of the city where he continued as Records Clerk until his demise in 1897.

From reaching the age of 60 years in 1892, Lucas had to annually reapply to continue to work as he had reached the civil service’s compulsory retiring age. Then, during 1897 he began to take sick leave; in June, one month, rather ominously suffering from a ‘throat affliction’; a little later, 15 days, then another month and finally placed on sick leave with full pay until his death on 21 November 1897 aged 65 years.

deNeufville Lucas, late Lieutenant, 40th Regiment, passed away at his home as a result of carrying Ensign Pennefather’s bullet in his tongue for eighteen years, a wound that became cancerous, causing death by epithelioma of the pharynx.

Here was a man who contributed to the colour of colonial life, who appears to have probably been well known and respected as he went about his military and public service duties yet, at the time of taking up his military career had little idea that he would be rubbing shoulders with the colonial elite and minor royalty and would die as the result of an obscure garrison incident in a colonial outpost.

Based on a paper deliver to the MHSA 2010 conference, Melbourne. Published in Sabretache Volume LI Number 3 September 2010

Contact AnthonyHarris about this article.