The First World War was a truly global conflict. It’s often forgotten with the emphasis on the Western Front and Gallipoli that most nations in the World were somehow linked and involved in the conflict. In India, Japan and China the ripple of European political leader’s egos was well and truly felt.

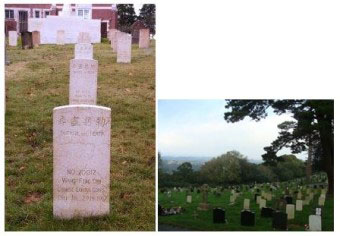

Last year whist visiting the Western Front I was in a small war cemetery and tucked away in a quiet corner was a single grave with Chinese writing. I did know that there were Chinese labourers involved in WW1 but really had no idea of why or how many. The story of how 140,000 Chinese labourers came to be involved in the Western Front is one that puts the global involvement of WW1 in perspective.

When the war was declared in the autumn of 1914 China was officially neutral. In August 1914 President Yuan Shikai had offered 50,000 Chinese troops to Sir John Jordan, the British Minister in Beijing, to help conquer the German enclave at Tsingtao.Jordan rejected the offer outright. This first offer to join the war by the Chinese is now seen as not so much an offer to join the Allies and abandoning the neutrality of China but as a national desire to expel the Germans from Chinese Territory. Leaving this issue to the British and Japanese would undermine China’s international status.

At this time the Japanese were pushing hard to seize any opportunity to increase their influence in Asia and they opposed any participation or involvement by the Chinese to regain their territory, in fact the Japanese only very reluctantly accepted the British involvement. Jordan’s rebuff greatly offended the Chinese leaders as it showed just how irrelevant the Great Powers viewed any role that China may play in the war. This rebuff reinforced the desire of Chinese leaders to somehow exploit the war and China’s participation which was seen as a means to enhance China’s international status.

The Japanese in this 1914/15 period were also vey aggressively determined to take advantage of the war at China’s expense, and in January 1915 presented ‘the infamous Twenty One demands’ to the Chinese Government. These demands were in principal a means of making China a Japanese vassal state. The demands consolidated existing Japanese influence in Shandung and Manchuria and enforced the appointment of Japanese advisors to all Chinese government departments including the police. Although disturbed by these demand on China, Britain and France could do little to help and on 9 May 1915 China ‘in a day of shame’in Chinese history had to accept the Japanese demands.

The national humiliation of the Japanese demands caused deep reflection by the Chinese leaders on the war and how China could somehow use the war situation to China’s national advantage. It was agreed that China should join the Allies in the war if only to be part of the peace process when it was expected that some of the Sino-Japanese issues would be discussed.

In November 1915 China formally advised Britain that they were prepared to join the Allies if they were invited by Britain, France and Russia. The Japanese were totally opposed to this offer on the specious grounds that it might ‘bring China to a state of disorder and devastation’. Sir JohnJordon advised in February 1916 that China was willing to join the Entente as a partner on a footing of national equality however the Japanese refused to accept these terms and the offer was refused.

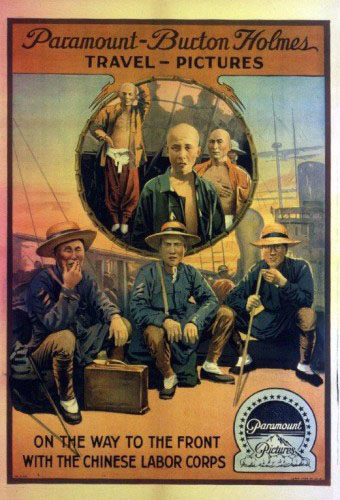

Faced with this Japanese veto, Liang Shiyi an advisor to the Chinese president Yuan devised a policy called ‘yigongdaibing’ [using labourers as soldiers]. While not full participants it was a plausible means to a clear and desirable political end. The British were sounded out about this option but it was a year before anything happened.

By early 1916 the British were beginning to experience a very serious manpower shortage both with the army and domestic war work. The Great Somme offensive in July 1916 furtherexacerbated this manpower shortage. Lloyd George the new British war Minister in August 1916 agreed that Chinese labour could be used in France.

In November 1916 Thomas Bourne a railway engineer with long experience in Asia was appointed to set up a recruitment base at Wei Hai Wei in North East China. It was accepted on experience in India that men from the cooler northern China would make better workers than their counterparts in the warmer southern China.Recruitment was slow at first but by the end of 1917 some 35,000 men had been sent to Europe and by the end of the war this figure had reached 100,000 men.

The French government was also recruiting from January 1916 and some 40,000 Chinese labourers were recruited by the French and sent to France by the end of November 1918. To preserve the fiction of Chinese neutrality a private concern ‘The Huimun Company’ was set up by a director of the Chinese Industrial Bank and Liang Shiyi [the advisor who devised the scheme]. They dealt with George Trupil a retired French army Colonel who operated the recruitment business. This private enterprise cover worked well and enabled the Chinese government to dismiss a complaint of the German Legation in Beijing that the scheme was violating Chinese Neutrality.

French recruited Chinese labourers began arriving in Europe in August 1916, they were transported by ship across the Pacific to Vancouver Canada then 6,000km overland to Halifax,Montrealor St John and then by ship to Europe. This was a long hazardous trip brought about due to the danger from German submarines in the Mediterranean. It is estimated that at least 700 men lost their lives getting to Europe. In one incident prior to the Pacific option being used. Over five hundred Chinese workers lost their lives when a German submarine sank the French passenger ship Athos near Malta on the 17 February 1917.

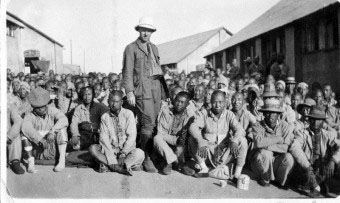

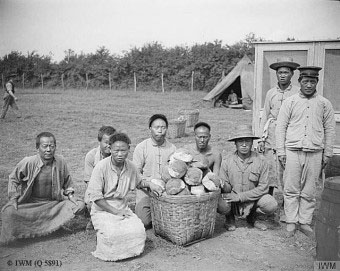

The French and British treated the Chinese labourers differently, the French workers tended to be better treated and paid and racism was less pronounced in the French camps. The French tended to be more relaxed with discipline and with no restriction placed on out of working hour’s activities. The British used strict discipline and gave little latitude to itsChinese labourers. The French and British Chinese workers were under military regulations, they wore uniforms and accommodated in barracks.In 1918 there was 17 Chinese Labour Camps in Northern France housing 96,000 men.

The work these 140,000 labourers performed was wide and varied from dock workers, road mending, factory work and ammunition handling. Even though the British had committed that they would not take part in military operation they often came under shellfire and enemy air attacks. The Chinese historian Xu Guoqi estimates that around 3,000 Chinese lost their lives during the war either on their way to Europe or due to enemy fire, disease or serious injury.There are over 2,000 Chinese Labour Corps war graves in Commonwealth War Graves cemeteries.France has 1864Chinese grave sites, Belgium 85 and surprisingly 20 in England.

First class ganger Liu Dien Chen was recommended for a Military Medal for rallying his men when under fire in March 1918, he was eventually awarded the Meritorious Service medal as it was decided that the CLC members were not eligible for the Military Medal. Five Chinese Labour Corp members were awarded the Meritorious Service Medal during WW1.

In March 1919 there were still 80,000 Chinese workers in France and Belgium with orders to clean up the battlefields. This involved digging up the bodies of dead soldiers and reinterring them in Military Cemeteries. There was a gradual return to China between 1919 and 1921 and it is estimated by 1921 only about 3,000 Chinese workers were still in France. This remaining group were the initial founders of Paris’s Chinatown district.

If you visit the Western Front in the future look out for a Chinese grave and pause for a moment to reflect on this aspect of WW1. These thousands of Chinese men so far from home with really no reason to be there except to make some income for their families in China now lying in the clay soil of France and Belgium. Another sad contribution of lives by a great nation a long way from the Fields of Flanders.

Contact Peter Fielding about this article.