Australians and New Zealanders tend to focus on Gallipoli and the Western Front when addressing land battles of the Great War.

This phenomenon has been reinforced by the 100-year centenary events that have just ended. Far less is known of other campaigns involving our troops and other volunteers (collectively called Anzacs in this review for convenience and not to be confused with ANZAC) who served in other theatres. The collective efforts of all such campaigns saw the Allies prevail in November 1918, and it is a brave person who might posit the relative value of each with a view to risk leaving any one of them out. Every such ‘sideshow’ from the main effort drew resources and prolonged the war by preventing either side to easily mass its assets for a decisive blow to end the war in less time.

The Serbian campaign’s principle purpose was the defence of Serbian sovereign territory against an enemy determined to over-run it, primarily to secure a land passage way from Germany to Turkey. Initial successful defensive efforts were followed by a withdrawal of the Serbian Army from Serbia until the eventual liberation of Serbia and the defeat off the Central Powers in that theatre.

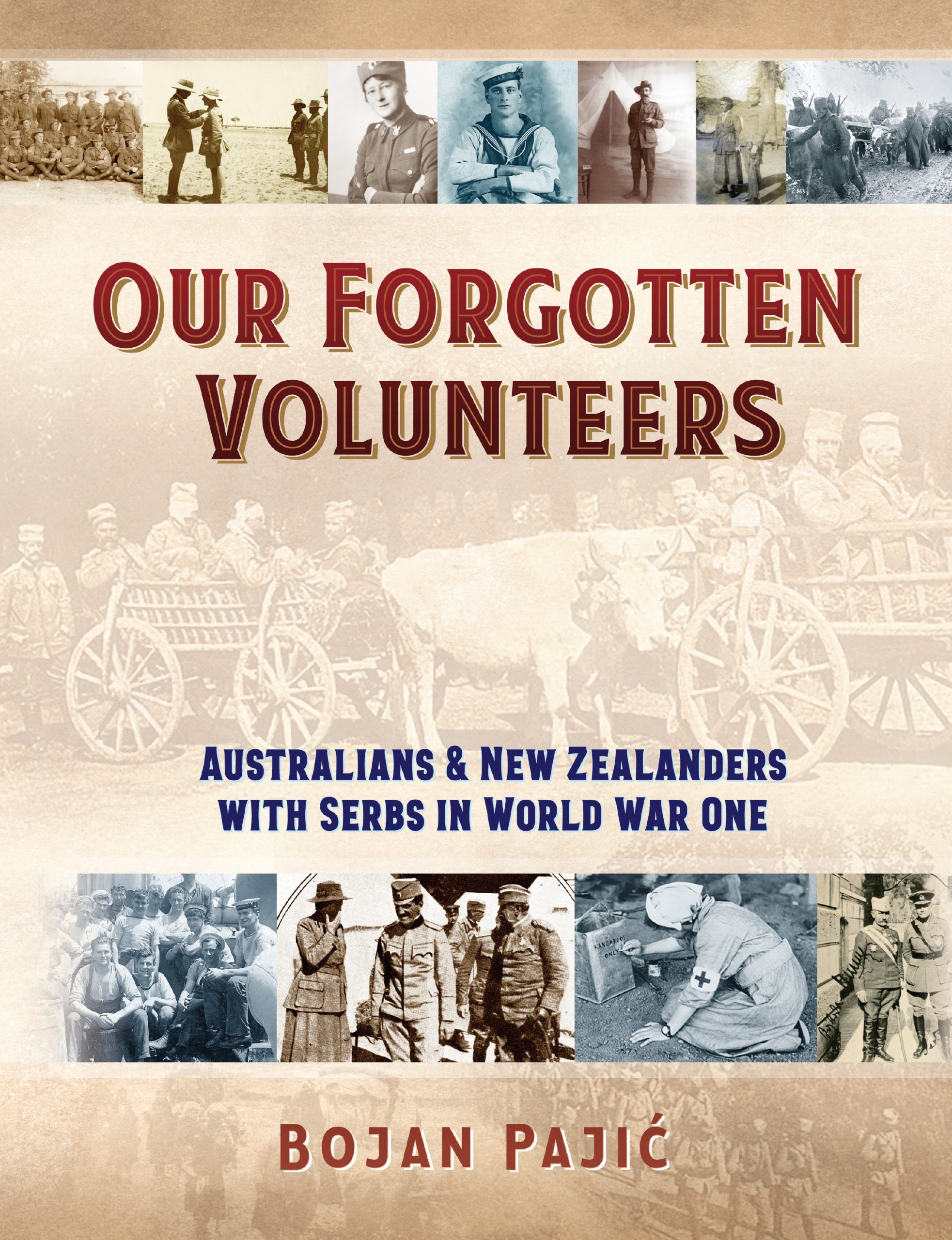

This publication, in part motivated by the author’s ethnic and Australian Service background, represents a remarkable effort in telling us the story of such a campaign, and the roles played in it by the Anzacs. Through a prolific effort by a team of researchers, the involvement of over 1,500 Anzacs are used, many with individual life profiles to underscore that effort. Pajic and his research team deliver a remarkable story that until know, has not existed in any comparable work. This book is a most important addition therefore, to the many treatises that already exist on Gallipoli, the Middle East or the Western Front and their battles.

Pajic succeeds with a most effective design and presentation of a slice of our military history that up to now has been a gap in the Australian and New Zealand literature on the Great War. The book outlines the chronology of the Serbian (aka Balkan) campaign in the context of the global war in an eminently readable format through chronological chapters supported by detailed Annexes. The first chapter outlines the key causes of the Great War and positions Serbia’s part in it, noting that Serbia was already engaged in a string of ‘local’ wars over several years leading into 1914, and had already suffered large numbers of casualties and damage. Subsequent chapters take the reader through the Serbian campaign in logical periods, weaving individual stories of the Anzacs as a clever and gripping means of telling the story of what they did, what it was like and how the campaign unfurled. He succeeds in a manner rarely achieved through this narrative method. Extensive diary extracts, letters, rich and varied photography, most never seen by this reviewer, present the reader with a dialogue that makes the book compelling and richly informative reading.

Anzacs served in Serbia in at least eight different categories of military and civilian support:

1. Members of non-military voluntary hospitals under the auspices of charitable organisations, comprising mainly women, a considerable number of which were doctors and nurses. Some were led by Australians, and often positioned close to the front lines. While not military units, these hospitals and their ambulance elements were effectively treated by the Serbians as though they were, so dire was the situation.

2. Australian nationals enlisted in British Army units fighting on the Salonica Front.

3. Members of two AIF units – a transport unit and a remount (horse) unit also fighting on the Salonica Front.

4. Members of the 1st New Zealand Stationary Hospital at Salonika.

5. Individual medical volunteers in support of Serbia’s war effort.

6. Crews of six RAN torpedo boat destroyers in the Adriatic Sea supporting the campaign.

7. Members of the Australian Army Nursing Service (which did accept women), deployed individually to a range of military units.

8. Australian and New Zealand nationals who served in the Serbian Army, the majority being ethnic Serbians; some started training with home armies before being shipped to Serbia and handed over to Serbian commanders.

One of many difficulties faced by the average reader and military historian alike is the collective paucity of knowledge of this campaign. It does not feature in either of Australia’s or New Zealand’s Official Histories of World War One, and the cultural differences of language and changed geographical naming pose a dilemma for most readers. Pajic’s book neatly addresses the changing name dilemma as the story unfolds. This reviewer is most grateful for the successful manner in which this was done; I was able to follow the name and border change narrative. This feature, together with sufficient maps of a generalised nature, allows the reader to readily follow the course of the war through the eyes of the Anzacs.

The Serbian people are repeatedly referred to by the informants in this story as gentle, appreciative, suffering silently in the face or enormous adversity. They were extremely gracious, pleasant and thankful to our volunteers, especially the women ambulance drivers and allied health care staff. A striking feature of the book is the large number of women who served, primarily in medical roles due to the fact that women doctors were not permitted to serve in the Australian and New Zealand armies. The Serbians, suffering dire shortages, had no compunction in employing women who wanted to contribute to the war effort: they had little capacity to provide their own medical support on the scale needed and gender mattered little. When armed conflict, including this one, are said to feature atrocities and offences such as rape and murder of civilians, there is no evidence presented of any such behaviour by the Serbian troops regarding our volunteers, many of whom were women and sometimes, entire hospitals so staffed, or in isolated locations where such a temptation must have been possible.

And so, under dreadful conditions and having to deal with the volume and array of horrendous wounds, rampant disease, shortage of supplies and under great risk of casualties themselves from enemy action, these women served in roles at least as valuable as the male combat participants. An interesting story is about two women who enlisted in the Serbian Army infantry, one of whose gender was only revealed when she was wounded. No other European army is known to have had women combatants in their infantry in this war (aside from Russia). The book contains numerous such revelations especially regarding the role played by women. Few Australians or New Zealanders, even descendants of the featured Anzacs, would know of these until they read the book.

Equally compelling in the narrative is the distinction made between the perception of the campaign as seen by the top-level adversaries (senior command) and the reality on the ground. Conditions were appalling, casualty and death rates very high and even basic war supplies so lacking as to be sometimes non-existent; eg transport, artillery, rationing and medical care. A phenomenon is the dilemma that many Serbian troops faced as they advanced or retreated: to obey orders and stay as formed units, or to leave and try to help their families/non-combatants survive in areas over which the battles raged with high enemy atrocity rates evident.

Use of Australian, New Zealand and Serbian sources during the research for this book results in excellent coverage of what was, for the Serbian people, total war with tragically high losses, but one which saw that nation eventually triumph along with the rest of the Allies. There are also many facts brought out in this book from which military planners have possibly learnt. One of the more obvious ones was the willing acceptance of women in medical support roles, especially doctors and drivers, roles considered in wartime to be ‘men’s work’. Another is the ruthless prioritisation by the allied high command in the allocation of forces. The Balkan Front received far less support from the British and French until well into the war during what most British military historians call the 1916 Salonika campaign, when the first AIF and NZ army units were first deployed there alongside Serbian, French, Italian, and British forces to oppose Austrian-Hungarian, German and from October 1915, Bulgarian forces. Sometimes, tough priority calls had to be made in the face of finite resources.

The research effort is simply staggering. 1,500 Anzac soldiers, airmen, medical volunteers and humanitarian workers are identified, and many of their backgrounds and involvement presented. Of these, over 150 were decorated by the Serbian Government. Doubtless, this book will prompt the identification of more Anzac veterans as readers note the significance of this line of research and the manner in which it has been carried out and presented. The text is rich in the Anzacs’ dialogue. The reader can feel as well as read the experience of those who deployed. It is a most successful technique, especially when interspersed liberally with Balkan battle scenes and individual photographs of the Anzacs themselves, some in-country, others back in Australia.

A most applaudable use of two Bibliographies – English and Serbian language – would benefit from a consistent format. Photograph crediting is inconsistent; some have only ‘AWM’ instead of featuring the conventional AWM number added. Others have no credit at all, with some accompanied by generalised captions which, while descriptive, could lead to a questioning of their authenticity. Fortunately, the number and freshness of the imagery far outweighs such potential criticism.

Serbian war losses were sickening. Page 270 lists these data, revealing the biggest loss of life in proportion to the country’s population of any nation to wage war on either side. 28% (or 1.2 million) of all Serbians died. 55% of the national infrastructure was destroyed. Yet they fought on, with their allies including the Anzacs, among them. And eventually to victory.

Pajic and team are to be congratulated on a Herculean effort in producing this most handsome volume. In an increasingly multi-cultural country, it may well be that this book will also inspire others to investigate and report on other ethnic groupings who have served. We would be a better nation for it, having such additions to the more widely understood histories of our mainstream, and prized, all-volunteer military contributions to world peace.

Perhaps the last word is embodied in this statement about the deployment of troops in Europe on the day the guns fell silent:

‘The German Army was still on French and Belgian soil and no allied soldier was on German soil. However, Serbian troops were now on Austro-Hungarian territory.’

And supporting them were ‘Our Forgotten Volunteers’.

Reviewed for Sabretache, Vol. 60, No. 1, Mar 2019: 54-57 by Lieutenant Colonel Russell Linwood, ASM (Retd)

Contact MHHV Friend about this article.