Part Two

On 13 November 1914 the Government moved against the Continental Tyre Company, calling a formal inquiry headed by High Court Justice Sir Isaac Isaacs in the first case of its kind under the Trading With the Enemy Act 1914. The Minister for Trade and Customs applied to the High Court of Australia to appoint a controller over Continental under the Act. The inquiry was ostensibly about investigating whether Continental was in contravention of the Act, but it also gave the authorities an opportunity to investigate Edwards himself.

Legal counsel called for affidavits and witnesses were called in – Edwards and the Continental company secretary and director James M. Campbell appeared as witnesses and grilled about the company operations and its links with Germany. In sworn affidavits, both Campbell and Edwards protested the Government barrister’s assertion that on instructions from Germany to remit money to Germany they would do so.

Edward’s affidavit confirmed that the statements made by Campbell were correct. ‘No money had been remitted since the war, and not any would be sent directly or indirectly.’ Much emphasis had been placed in the Government’s affidavit of the fact that three of the directors and most of the shares were held by Germans in Germany, yet there was no structural connection between the Victorian Limited Company and Continental in Germany.

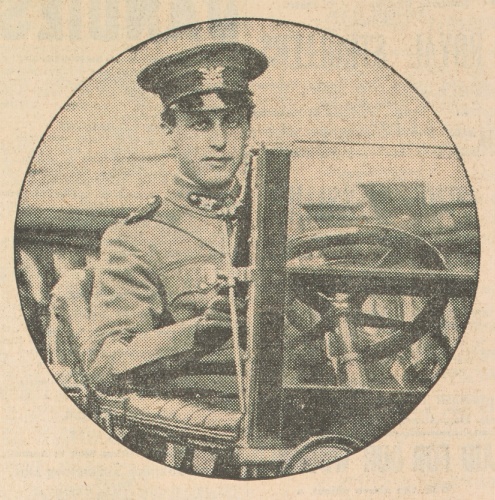

The opposing barrister’s assertions had been rebutted in a steady and factual way. The barrister instead turned on Edwards himself. Here was the true purpose of the inquiry – not to get Continental, for that was already pre-determined (the court already knew who would be made the Controller before the case was heard, based on the immediate appointment at the end of the case), but to get Edwards. An objection by Continental’s counsel was overruled by Isaacs. The opposing barrister began by raising innuendo that Edwards was clearly up to no good when he became an officer in the Automobile Corps, but quickly abandoned that line when Edwards again responded factually, and Starke could provide no substance to support the line of questioning. Then came the real ambush – reading to the court translated excerpts from letters written to his mother in Germany via Holland – and an opportunity to discredit Edwards completely.

The translations, obtained in secret from the Censor’s office in the GPO Melbourne, were not apparently provided to Continental’s legal team – presumably on the basis that it was not to do with Continental rather with Edwards. Edwards was not of course legally represented in court as an individual as the inquiry was about Trading with the Enemy. The original German language letters have not been found in archives, so it is impossible to check the veracity of the translations or the context in which the excerpts were written. Edwards was given certain translations to read. In these letters [Edwards] referred to the spy fever in Australia, and the throwing of dirt against the Germans. He referred to Australia as an enemy’s land, to the doings of the Emden, and the hope for news of German victories. In short Edwards ‘expressed views which indicated that his sympathies were still with the country of his birth.’

The Government must have been delighted to be able to introduce this ‘evidence’ in court to undermine Edwards’ credibility and so be able to be seen to act decisively against a German trading firm and under the new wartime legislation, against its managing director, a naturalised British subject who could be smeared as disloyal and untrustworthy, so hitting two birds with one stone.

Indeed, the Government had sought a legal opinion on the letters as early as 27 October 1914, evidence that it had Edwards in its sights early on but had to wait for the relevant legislation to be enacted before it could act against him. Isaacs, ignoring all the of Campbell’s and Edwards’ testimony re not ‘trading with the enemy’, decided that Edwards might break the law.

Edwards could not be trusted not to break the law, based on a few short paras – injudicious though they may have seemed – in private letters to his Mother which Edwards himself knew would be going through the censor and even though it was physically impossible for him to remit any funds to Germany without the willing cooperation of the other two Australian directors. Later it was inferred that he wrote the letters through a New York contact to avoid the censor, because he made disloyal statements. A more reasonable explanation was that he simply was trying to get letters through to his Mother to whom he was clearly devoted, in any way he could, and knew that they could in any event go through the censor. After all, he could hardly write to his Mother in Germany expressing pro-Allies sentiments as that would have potentially placed his Mother and family in jeopardy themselves from the German censors.

Even though the company was a properly registered Victorian company and there had been no attempt to repatriate profits to Germany after war had broken out, and despite the strong and clear refutation of any suggestion that monies would be repatriated, or that the company would act in any way contrary to the law, the Government nonetheless moved to appoint a controller of the company and effectively take it over.

Reading the excerpts of those letters today, one cannot avoid the impression that whatever the statements made in the climate at the time by Edwards, they were completely at odds with his public life in Victoria and his genuine business motivations. Edwards lived and breathed the auto business; he was not ever political. Edwards seemed shocked by the surprise attack on him in Court – it was an ambush but also a deadly one to his reputation. Even if Edwards in the first flush of war was sympathetic to Imperial Germany as expressed in his private letters to his mother, what is equally clear is that Edwards and Campbell and Selby, the Australian directors of the Company were more interested in maintaining the company’s business and stability than taking sides in the war. The chosen interpretation of his comments in two letters damned him nonetheless in the court of public opinion and his fate was sealed. In the letters Edwards himself explained to his mother that letters were going through the censor – it seemed, given that, he was naive to think his comments might not be misinterpreted – with terrible consequences for himself, and Continental.

In contrast to the impression created by the Government’s barrister about Edward’s motivations and loyalty, there is also an interesting letter from one of Edward’s British-born New Zealand employees on Edward’s internal security file, dated 5th November 1914. The employee, resigning as he could not work for a firm parented in Germany, nonetheless spent considerable time to thank Edwards, express his regrets and then state that he had ‘realised of course that your [Edwards] natural sympathies are as quite as much with England as my own…’ When the letter was passed by Defence Intelligence and in turn to the Attorney-General, the contrary statements as to Edwards’ loyalties were not investigated further and certainly did not make into the press.

Edwards was, according to the inquiry, ‘disloyal and disaffected’, with the implication that his very attempts to be an effective businessman with an Anglicised name since 1904 was part of a scheme to support the Kaiser. His work with AVAC further implied he was some sort of spy, infiltrating the senior military officer corps and discovering the secrets of Victoria’s road systems. As late as 1919, preposterous claims in the scurrilous press even claimed that when Edwards was with AVAC maps of the States had been hidden in the backs of Continental Tyre advertising boards around the country (presumably to help the German invasion)! His security file showed otherwise – they were simply advertising postcards issued in each State with a map of that State on the back. It was probably not a surprise to him that not one of his many friends and supporters made over the years in Victoria came forward to defend him.

He barely had time to resign from his formal memberships on his return before the Government arrested him on 19 November, stripped him of his commission as an officer in the Automobile Corps and interned him under the War Precautions Act. He was held initially in the military barracks on St. Kilda Road and then moved to a hastily designated internment camp at the Langwarrin military training facility on the Mornington Peninsula south east of Melbourne. It was the same camp he had, as a Volunteer officer, frequented in 1909 as part of the Easter militia camp of that year. He was disgraced; the life he had worked so hard to build up with his family in Victoria was swept away.

The popular press, both conservative and working class, was quick to attack Edwards as part of the emotional response to the war and the strongly held pro-British sentiment that prevailed.

The public also chimed in with letters of concern to the authorities about Edwards’ apparent hidden agendas. Edwards had obviously been up to no good.

The Government decided, partly due to cost and resources, to centralise all detainees at the Holsworthy (later Holdsworthy) Concentration Camp in Liverpool, Sydney. Rumours quickly reached the prisoners that the authorities were planning to move Langwarrin internees to NSW. In July 1915 Edwards applied for an enquiry under the ‘Suspected Persons Inquiry Order 1915’, along with nine others, for permission to stay at Langwarrin and not be moved or be released on parole. They argued that their homes and families were in Melbourne and that it would place undue hardship on the families if they were moved – they promised to pay for their own upkeep if allowed to stay.

The officer commanding the Langwarrin Prisoner of War Depot even recommended Edwards be kept on maintaining records at the Langwarrin Venereal Centre nearby – Edwards, he wrote, ‘gave absolutely no trouble at all.’ The appeal fell on deaf ears. Writing to the Secretary of Defence, Colonel Robert Wallace, Commandant of the 3rd Military District, stated that the release of Edwards was not recommended, claiming ‘the matter would excite considerable public feeling.’ The application was refused on 2nd August 1915. In late August 1915 Edwards, and other internees from camps across the country were moved to Holsworthy in NSW.

Mrs Edwards subsequently moved to Sydney with the boys in early September 1915 to be nearer her husband, but on 14th November, 1915, according to newspaper reports, ‘feeling keenly the Isolation caused by her husband’s Internment and his position, Mrs Edwards fretted herself into a serious Illness, and died, lonely and broken hearted…..’ The boys were isolated from their father and raised by a surrogate.

And what of Edwards himself? He became a ghost, disappearing from the public record for four years between August 1915 when he was transferred to Holsworthy from Langwarrin until he was forcibly deported in July 1919.

The anti-German press, especially the so-called ‘yellow press’ like Truth (where truth was the last thing it sought), continued to hound German-Australians and their descendants through the war, especially if any had any sort of official work. Edwards remained a ‘poster boy’ for the German targets. In February 1916 Truth ran a long story under banner headlines:

“WITHIN OUR GATES.”

HUNTING OUT THE HUNS.

…in a case like the notorious one of Edward Edwards, the manager of the Continental Rubber Company, there was no evading decisive action.

This snake in the grass, whose real name is Eichengruen, and who had been on a visit to Germany not long before the war broke out, had worked his way into the responsible position of major in the Automobile Corps of the Commonwealth Military Forces, thus gaining possession of information that would have been of the utmost importance to an enemy force landing in this country. How much of this information he placed at the disposal of the war lords in Berlin, so that it might be available in the event of any mishap to Australia rendering it possible to land a German force in Australia, will never be known.

And he might have carried on his double-dealing for goodness only knows how long had it not been for that boastfulness that has been the downfall of so many blackguards. With all his shrewdness, he had not reckoned on the ubiquity of the censor, and thus there came to light his letters to his mother in Germany, crowing over the initial Hun successes in Europe, deploring the dislocation of business arrangements and praising up the work of the Emden, and expressing the wish that there were a dozen more like her at the same game. On the face of this, there was nothing for it but internment, though that punishment fell most heavily on the Australian woman who thought she was his wife, and who, ostracized, died recently of a broken heart.

While all of this was going on, and with the war evidently ending in favour of the Allies, the Australian Government in October 1918 set up an Alien Committee to consider what to do with the Germans and other ‘enemy’ prisoners of war and internees after hostilities were concluded.

The Committee came straight to the point with regard to those like Edwards:

We have … no hesitation in recommending that all interned alien enemies and denaturalized persons of enemy origin who, prior to internment, had made their homes in Australia or were temporarily resident here for the purposes of business, should be compulsorily repatriated. We think, however, that all persons whom it is proposed to repatriate compulsorily should be allowed to appeal to a special tribunal.

Adding that, ‘German merchants and importers should as a rule be deported.’ Soon after, in a letter dated 28th January 1919 to the Secretary of the Department of Home & Territories, the Secretary of the Defence Department recommended that Edwards or ‘Schengruen or Eichengreen’ [sic] be de-naturalised on the poorest of reasons – three paragraphs from letters he had written to his mother in 1914.

On 1st February 1918 in a Government Minute entitled ‘Re-Denaturalization’, Edwards appears on list ‘A’ of 21 Germans in Victoria who had been interned during the war and who are slated for de-naturalization – the Government had already decided to de-naturalise Edwards even before they set up the committee to consider repatriation.

Edwards’ fate was once again sealed – he could have appealed but he would not be allowed to stay. Although he fell under the class of ‘merchant and importer’, remarkably he was not in fact ‘de-naturalized’. This had not occurred automatically in 1914, and now the Government scrambled to do so, to prevent any possibility of an appeal. One reason for the Government to act was that in March 1919 it appointed a Royal Commission to review the cases of those internees who were appealing against deportation – and it wanted to give no chance for someone like Edwards to appeal, let alone successfully.

Meanwhile Edwards finally learned of his fate – he and his two young sons were to be compulsorily deported to Germany. He had been subject of a process that in general was ‘…..erratic and arbitrary, being subject to continuing public hostility and the attitudes of the military and intelligence bureaucracies which were often punitive and vindictive.’ In Edwards’ case, there seems to be little doubt that it was both punitive and vindictive with some press continuing to smear his name as late as 1924. Even if Edwards could have appealed the decision, why would he have? There was no good reason to try and stay.

On 27th May 1919, Edwards, along with 987 others were put on board the ss Kursk and it sailed via Durban and Rotterdam where the internees were put ashore for Germany. The sailing of the Kursk further underlined the fact that in Edwards case, he was especially singled out. Not only did the sailing take place before the appeals procedures had been put in place but also, the vast majority of those on board Kursk were German citizens who were to be deported anyway. Edwards was one of six former ‘Naturalised British Subjects’ on board the ship – he was joined by an architect, a waiter and a cook from NSW, and a draftsman and a public servant from Queensland. Clearly they were a major threat to the British economy of Australia. The children on board the Kursk were not named, and we can only assume that special arrangements had been made to get Edwards’ sons on board. Even then, nearly 20 people on board died of influenza and were buried at sea; Edwards and his sons were not among them.

In March 1920, the Brisbane Telegraph cited Edwards in a longer article under the headline:

Spies in Australia.

CLEVER AND RESOURCEFUL.

Despite the headline the article could not detail a single case of an actual spy in Australia, but decided Edwards was as close to one as Australia had. Once again going over the issue of the letters to his mother in Germany in 1914 and his captaincy in the AVAC, the Telegraph tried hard to pin something on Edwards to prove its point and claimed that it was Edwards who requested the Court of Inquiry in November to allow him to disprove allegations against him when in fact it had been the court who had called up Edwards as a witness in the case against Continental under the Trading with the Enemy Act. In discussing the letters, Edwards ‘gloried in the doings of the raider Emden’, and expressed ‘feelings of the greatest hatred for the enemy’s land in which he was compelled to live’. The article said one thing which was very close to the actual truth – ‘His internment was a severe shock to many people who had known him and believed in his loyalty’ but added that ‘he was as plausible as he later proved to be dangerous.’ [author’s italics all] Finally – ‘Many other cases might be quoted to show that the German seldom changes…..’

The so-called ‘yellow press’ in Australia could not let go of Edwards either even after he had been forcibly deported, with two articles referring to him as ‘that German Jew’ while another inflammatory article in 1924 inserted against the story a caricature which would become common under Nazi Germany in the 1930s, without caption, while carefully not mentioning that Edwards was of Jewish heritage. This article attacked Edwards in a cowardly and blatantly racist misrepresentation.

This racist description is completely at odds with everything known about Edwards. Of interest was that the journalist who wrote the article admitted that ‘our informant, who appeared to have a personal grievance against Edwards, …..came across with gusto. ‘Edwards’, he said, ‘was a naturalized German, and the company was a German concern, for which reason he and other business men were refusing to pay their accounts.’ The informant was almost certainly the editor of the Motorist, Horace W. Harrison, who held a particularly strong grudge against Edwards.

In the wake of the ss Kursk, Edwards left Australia with his life in tatters. He had lost everything – wife, business, investments and reputation. He left with the clothes on his back and his two young teenage boys, whose experience of the terrible years of the loss of their mother and the

incarceration of their father would no doubt stay with them forever. While could return to his family in Germany and try to recover from the travails of being interned, the loss of his wife and the end of his business plans and hopes for Continental in Australia, he was returning to a very different Europe than he had left 25 years earlier.

Edwards was evidently neither part of an espionage ring or a spy inserted into Melbourne as for Prussian conspiracy to infiltrate Australian society to steal secrets for the Kaiser. On the contrary, like many others of German descent settled in Australia he simply wished to assimilate and build a successful business and life for his young family. His own anglicised name, his two locally born sons with their English first names, his business focus and world outlook, his work as a long-standing committeeman of the ACV, his naturalisation, his involvement with AVAC as a militia officer were all signs of his intentions to remain in Australia as a good citizen. In fact, his apparent lack of Deutschtum was a distinguishing feature of his life in Victoria. Not a spy but certainly another casualty of the war and times.

© Dr Andrew J Kilsby – This article is drawn from the book The Case of Eichengruen-Edwards and Continental Tyres

Contact Andrew Kilsby about this article.