Introduction.

When Japan made her sneak attack on Pearl Harbor on Sunday December 7th. 1941, not only did she precipitate the United States into WW2, but they probably decided their own fate in the war they had started in the Pacific.

The Pacific War.

At the start of the Pacific War, the Imperial Japanese Navy had the largest and probably the most capable Submarine Fleet in the area. 63 Submarines including 46 I Class, big boats by both British and US standards, some 2,900 tons, and crews of 100 or more.

At least 27 of the I submarines made one patrol in Australian waters, and some made two, in total 40 patrols were undertaken around our coastline.

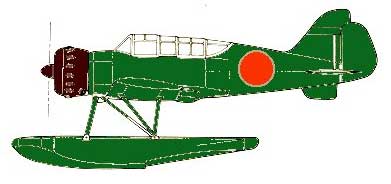

For the Japanese, their I Class were considered to be maids of all work, some carried a floatplane, or a midget submarine secured to the casing, they laid mines, sat off enemy ports and collected weather data, they attacked our Merchant Shipping, and were used to bombard shore installations.

Later in the war they were in my view ill-used, stripped of their weapons, they became mere cargo boats, hauling supplies around the South Pacific.

Australia under Siege.

From bases such as Penang, Surabaya, Truk, and Rabaul, these submarines sallied forth to harass and destroy our shipping. They ranged widely, attacking shipping off Fremantle and Shark Bay, laid mines off Darwin, and in the Torres Strait in Northern Queensland, in the approaches to the Brisbane River, they lay in wait for victims off King Island in Bass Strait, off Cape Otway, and on the east coast of Tasmania.

Their scout float planes flew over Melbourne, Hobart and Sydney, and Newcastle and Sydney were both shelled from seawards.

Port Gregory, a small settlement on the Western Australian coast was also shelled, perhaps its name had something to do with its relative insignificance. It was on our east coast that the Japanese submarines wreaked the most havoc, 17 ships were sunk including our Hospital ship Centaur, and 268 lives were lost, she was clearly both painted and illuminated as a Hospital ship, but was ruthlessly attacked.

Torpedo Armament.

These I Class submarines were I believe, equipped with the finest torpedo to be found in any Navy worldwide.

Both Germany and the United States Navies experienced dreadful problems with their torpedoes not exploding on impact, or running deeper than the depth at which they were set. It took some time for the ordnance departments in both countries to accept a problem existed, and then to fix them.

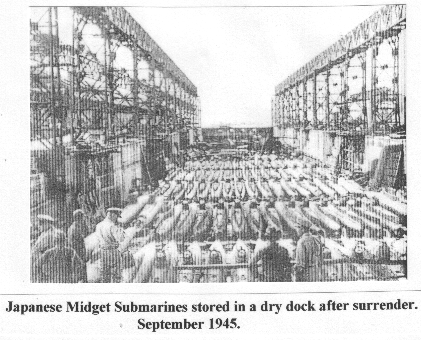

Japanese Wartime Submarine Construction.

A further 126 submarines were built after 1941, conversely the IJN submarine service suffered the loss of 131 boats destroyed in WW2.

By contrast, The US lost 52, the British 75, Italy 82, Russia 109, and the German Navy, an incredible number of up to 785.

You may find higher figures quoted for both Italy and Japan, but when I was writing my “Underwater Warfare. The Struggle against the Submarine Menace 1939-1945. “I corresponded with the Italian Defence Department in Rome, and also with the Japanese Naval Attaché in Australia, and the figures I have used above relate to their response.

The Midget Submarine.

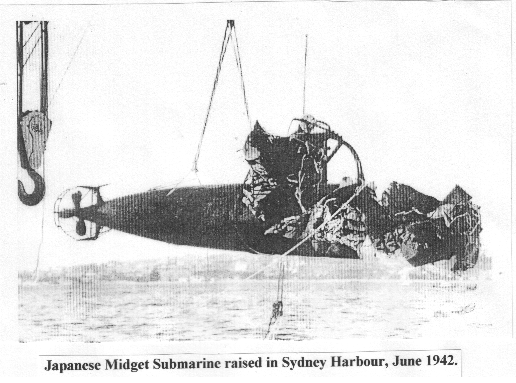

Back in the 1930’s, Japan had started work on producing a Midget Submarine, about 24 metres long, designed to carry a two man crew, plus two 18 inch torpedoes (that size refers to the torpedo diameter) in two forward tubes.

These Midgets were to be clamped to the deck of an I Class boat, and five such Midgets were used in the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, but all failed in that mission.

Mine laying off Australia.

By the end of January 1942, four Japanese mine laying submarines had laid their deadly cargo of 126 mines around Darwin harbour, in the Joseph Bonaparte Gulf, close to where the Ord River reaches the Indian Ocean, and in the western approaches to Torres Strait.

Despite this major mine laying effort, I am not aware of any reported victims.

Three of these four Japanese Submarines were involved in attacks on our shipping, and I-124 was sunk off Darwin on January 20th. 1942. Our corvettes Deloraine,Lithgow, Katoomba and the US destroyer Edsall were all involved in her demise.

Darwin attacked from the Air.

In February of 1942, both 1-121 and 1-122 were back sitting on our northern coastline to send off weather reports to their bomber strike force.

On February 19th. Darwin suffered the first of many air raids from Japanese bombers, they sank USS Peary and several merchant ships in the harbour, the Hospital ShipManunda survived this attack.

Broome was also attacked from the air early in March, war had indeed come to mainland Australia.

Japanese forces sweep south.

Hong Kong then Singapore fell, the Dutch East Indies was under dire threat as Japanese forces swept southwards, carrying all before them. Indeed our country was threatened with invasion for the very first time in its history.

I-25 with her float plane sailed from her base in mid Pacific on February 5th, bound for our east coast, her CO, Lieutenant Commander Tagami ordered to reconnoitre Sydney, Melbourne and Hobart, and to report by radio any shipping concentrations in those ports.

By February 14th, he was off Sydney and he sailed some 100 miles South East to launch the float plane early on the morning of Tuesday the 17th, the pilot, Warrant officer Nobuo Fujita.

Whilst Sydney peacefully slept, the float plane flew over the cliffs at La Perouse just as daylight seeped over the eastern horizon. In the Harbour 23 ships were counted, a large warship with three funnels was noted at No 1 Buoy (that was the County Class heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra, and I was serving in her as a Sub Lieutenant) nothing stirred.

As the sun rose, the float plane now flying at only 50 metres flew back to her mother submarine, and by 0730 ( 7. 30 AM ) had been recovered.

I-25 moved South, and now her floatplane flew over both Melbourne and Hobart.

Attacks off Western Australia.

Also in February 1942, three I-Class submarines moved down our West coast, with I-2 sinking the Dutch ship Parigi off Fremantle on March 1st.

The Midget Submarine attack on Sydney Harbour May 31st. /June 1st.1942.

In wartime, the element of surprise is forever paramount, and, to this end, over the period of 1939-1945 that embraced WW2, four nations sought to exploit that fact by developing both Human Torpedoes and the use of Midget Submarines.

These countries were: Britain, Italy, Germany, and Japan.

The approach to Sydney.

On May 11th. 1942, the Japanese 8th. Squadron of Submarines, I-22, I-24, I -27, and I-28, having been involved in the Battle of the Coral Sea operation were ordered to Truk to embark midget Submarines, as it was planned to attack Naval targets at Suva or Sydney.

Two floatplane carrying submarines, I-22 and I-29 were on their way to reconnoitre Suva and Sydney.

I-28 did not make it to Truk, she was sighted on the surface by the US submarine Tautog, enroute from Pearl Harbor to Fremantle in West Australia, two torpedoes despatched the Japanese boat.

The other three I Class all with midgets clamped to their decks sailed from Truk for Sydney about May 20th.

These Japanese submarines were: I-21 ( carrying a floatplane ) I-22 ( carrying midget No 21 ) I-24 ( carrying Midget A, it was given this designation as this craft was not recovered at the time of the attack, and her number was unknown ) I-27 ( carrying Midget 14 ) finally I-29 ( probably carrying a damaged floatplane. )

On May 30th. at about 0420 ( 4.20 AM ) a single floatplane burning navigation lights flew over Man of War anchorage in Sydney Harbour, then circled USS Chicago secured to No 2 Buoy, I was of course still in HMAS Canberra serving as a watch keeping Sub Lieutenant, we were secured to No 1 Buoy.

In due course, an air raid warning was issued, but searches by fighter aircraft turned up nothing, and the incident did not trigger any special defence measures. Post war it was learned that the float plane came from the Japanese submarine I-21, and her pilot, Lieutenant Ito, flew up the harbour at 600 feet, sighted Chicago and four destroyers in the Man of War anchorage, Canberra in Farm Cove, he then flew back to his submarine, but on landing close by in rough water, crashed his aircraft which sank. He and his observer were picked up, and they reported “A Battleship and Cruisers in Harbour.”

It would seem most likely that the cruiser USS Chicago, with her quite heavy superstructure was mistakenly reported as a Battleship, but from the pilot’s message the die was cast. It was decided to attack the next day, May 31st. 1942.

Boom Protection across Sydney Harbour.

The boom safety net at Sydney was designed in January of 1942, and its construction began that month. It was located at the narrowest point of the inner harbour entrance, between George’s Head, on Middle Harbour, and Green Point on Inner South Head, this protective net was not actually completed until July.

The single line steel Anti-Torpedo net was supported between piles, the centre portion was complete, but there were still large gaps at both East and West ends, at the Western end unnetted piles were in place.

Eight Magnetic Indicator Loops were in place across the sea floor of the Inner and Outer harbour entrances, the Loop produced a signature when a vessel crossed over it.

Midget 14, commanded by Lieutenant Kenshi Chuman with Petty Officer Takeschi Ohmori, was the first inward crossing recorded by the Loop system at 2000 ( 8 PM. )

With all the ferry and other traffic passing over the Loops, its significance was not recognised.

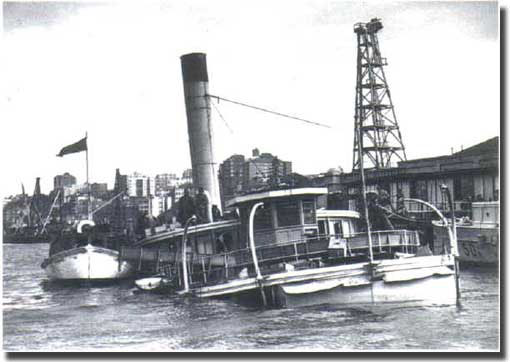

About 15 minutes later, Mr. J. Cargill, a Maritime Services Board Watchman, reported a suspicious object trapped in the boom net, with his assistant he investigated this object from a skiff which they rowed over to the scene, and he reported to Lieutenant Eyers, an RANVR officer in charge of the patrol boat HMAS Yarroma.

Eyers did not close this object fearing it may be a Magnetic Mine, but he sent off a Stoker in a skiff to investigate, and it was 2230 (10.30 PM) an hour and a half later after Cargill first reported his discovery before Eyers reported the object trapped in the Boom net was, in fact A SUBMARINE, then he sought permission to open fire. All quite beyond belief.

But Lieutenant Chuman, hopelessly entangled in the net, solved this dilemma for all concerned, he fired demolition charges which both destroyed the Midget Submarine and her crew of two.

Meanwhile, Midget A, with Sub Lieutenant Katsushisa Ban, and Petty Officer Marmoru Ashibe, and Midget 21, with Lieutenant Keiu Matsup and Petty Officer Masao Tsuzuku on board, had been ordered to follow Midget 14 at 20 minute intervals. Ban also registered a Loop crossing at 2148 (9.48 PM) and he proceeded up the harbour with USS Chicago as his prime target.

At long last some action was forthcoming, the “General Alarm” was ordered at 2227 (10.27 PM) by Rear Admiral Gerald Muirhead-Gould, Royal Navy, the Naval Officer in Charge at Sydney.

Ban was having problems with the depth keeping behaviour of his Midget, it kept breaking the surface, and lookouts in Chicago sighted him, but Ban managed to submerge as the cruiser opened fire with a 5 inch gun, but the submarine was too close to hit. The corvettes Geelong and Whyalla alongside the oil Wharf at Garden Island sighted Ban’s conning tower, 20mm fire from Geelong, and searchlight searches from both these ships proved abortive.

By now, the third Midget was approaching the Anti-Torpedo Net area, but Lieutenant Matsuo was having his problems with the trim of his boat, and he was sighted by the unarmed Patrol Boat Lauriana, then Yandra attacked with a 6 charge pattern of depth charges, after a series of explosions, Midget 21 was not seen again.

Flood lighting illuminated the scene nicely, no one had thought to order them to be extinguished up to now, and they silhouetted Chicago very well. Finally these lights went out at 0025 (12.25 AM, now June 1st.)

Ban was now in position to sink Chicago, only 800 metres from his juicy target, he should not miss as he set his torpedo to run at a depth of 2.4 metres, Chicago was 170 metres long, with a draft of 7.6 metres, Ban fired, once the torpedo left the tube, the Midget lost stability, it’s bow breaking the surface, and Ban took some 2/3 minutes to regain trim.

His torpedo veered off course, passing well ahead of Chicago, went under the Dutch Submarine K-9, now under an old Sydney ferry HMAS Kuttabul, berthed alongside Garden Island, and used as a Naval accommodation vessel.

The torpedo finished it’s run by striking the retaining wall, exploded, lifting Kuttabul high out of the water coming to rest on the bottom, 19 Australian sailors and 2 British sailors died.

Ban now fired his second torpedo at Chicago, but it missed by some 4 metres, and ran aground on the east side of Garden Island without blowing up. By now the harbour was in absolute turmoil, I can recall ships and small boats rushing all about, searchlights seeking a target, guns being fired, and no one really knowing what was going on.

Captain Howard Bode of Chicago had been ashore dining with Rear Admiral Muirhead-Gould, hastily returned to his ship, decided he had enough of this chaos within Sydney Harbour, and took his cruiser to sea, obviously unaware that there were 5 I Class Japanese submarines lurking off Sydney Heads, hopefully waiting the return of their victorious Midgets.

Back to the Midgets within the harbour.

Midget 21 had not been sunk by Yandra, she was found in Taylor’s Bay, and was then battered by attacks from both Steady Hour and Sea Mist. Later on June 1st. Navy divers found this Midget on the harbour floor, both torpedoes jammed in their tubes, and the propellers still slowly turning. One of the divers used was Able Seaman Jack Greening, a cousin of mine.

A registered Loop crossing was recorded at 0158 ( 1.58 AM ) and the subsequent analysis showed that this was an outwards crossing, it could well have been registered by Midget A, with Ban making good his escape after his abortive attempts to sink Chicago. Ban and his crew member did not rendezvous with their Mother Submarine, they were never found and their actual fate unknown.

Early in 1997 there was a report that a metallic object had been located in the ocean off Cronulla, there was much speculation that it may be the remains of Ban’s Submarine, but nothing came to pass in this regard.

The History of the Royal Australian Navy in WW2 records: “Luck was certainly on the side of the Defender, and was undeserved in the early stages, when inactivity and indecision were manifested.”

On June 9th, 1942, at 1100 ( 11 AM ) the four bodies of the crewmen from the two Midgets sunk during their attack on Sydney, were cremated at Sydney’s Eastern Suburbs Crematorium, accorded full Naval Honours, their ashes returned to Japan. A memorial plaque for those who took part in this daring but unsuccessful raid on our shipping on May 31st./June 1st. was unveiled at Garden Island. Sub Lieutenant Ban’s mother made the trip from Japan to be present at that ceremony.

Post attack.

After the Midgets failed to return, four of the five waiting submarines were ordered to go after Australian shipping, the fifth I-22, went off to seek victims off New Zealand and Suva.

Wreck of Japanese Midget Submarine M-24 that attacked Sydney Harbour in 1942, found at last.

When I earlier wrote that Ban’s Midget was never found, I had no idea of what was soon to be revealed.

Now at last, a group of weekend Scuba divers were on the cusp of creating Australian Naval History. They had chanced upon the wreck of an A Type Submarine, now identified as M-24, she rests on the bottom in about 70 metres of water, at Long Reef, a few kilometres off Sydney’s northern beaches. This rather motley crew of seven who call themselves “No Frills Divers ” have resolved a 64 year mystery of what happened to the daring crew of two, Sub Lieutenant Katsuhisa Ban and Petty Officer Mamoru Ashibe, and their craft.

Ban’s brother in Japan.

Katsuhisa Ban has a brother still living in Japan, who has always wished to know the fate of his late brother.

Our 7 divers met with Commander Shane Moore RAN, the Director of the Naval Heritage Centre located on Garden Island, he confirmed that this find is indeed the third and previously missing Midget Submarine M-24, that attacked shipping in Sydney Harbour over the night of May31st. /June 1st. back in 1942.

Reaction in Japan.

How the Japanese Government may react to this find, one may but speculate, will they want to raise the wreck, and then finally lay to rest these two very brave Japanese Sailors?

Thus the last page closes on a 64 year old mystery that many Naval and ex Naval personnel, including myself thought would never ever be solved.

Sub Lieutenant Ban was very unlucky not to bag USS Chicago, and perhaps even my own ship HMAS Canberra that wild night in May back in 1942. Somehow the defence of Sydney Harbour muddled through, we were extremely lucky to get away with just HMAS Kuttabul as the only victim, it was still tragic that 21 Sailors died from the attack.

Action on our Coast.

On June 3rd. 1942, the 4,734 ton Age, sailing from Melbourne to Newcastle ran into I-24 laying in wait, her CO made a surface attack at about 2100 ( 9 PM ) but his torpedo missed, now he attacked with his deck gun, again no result, as Age scurried off to the safety of Newcastle. Later Iron Chieftan was found, and torpedoed on her port side, she was gone in 5 minutes, and 12 crew died.

I-27 sitting off Gabo Island attacked the freighter Barwon, but this torpedo passed under the ship, then Iron Crown filled with manganese ore from Wyalla and destined for Newcastle was sunk, and only 5 of her crew of 42 survived.

Newcastle and Sydney attacked.

On June 8th. Japanese Submarines stood off Newcastle and Sydney to bombard them, but only one shell from I-24 exploded at Rose Bay, demolishing part of a house.

I-21 attacked Newcastle but no causalities and little damage, the end result.

Convoys implemented.

To counter submarine attacks on our shipping, those vessels over 1,200 tons and a speed of less than 12 knots were formed into coastal convoys with air cover.

List of Ships sunk.

Iron Crown, on June 4th. by I-27.

The Panamanian Guatemala, on June 12th. 40 miles NE of Sydney, by I-21.

George S Livanos, on July 11th. by I-11.

Coast Farmer, on July 21st. by I-11.

US Liberty ship William Dawes, on July 22nd. by I-11. The wreck found by a Sydney Dive Team in 2004, but that is another story in its own right.

I-175 torpedoed Allara with a full load of sugar on July 23rd. it struck the ship right on her stern, the force of the explosion blew her stern gun over the side, killing four of the gun’s crew. The ship was saved and towed into Newcastle.

On August 4th. I-32 enroute from New Caladonia to Penang, when 200 miles SSE of Esperance ran into the freighter Katoomba, shelled her, but the very rough sea did not aid the Sub’s marksmanship, and the freighter escaped unharmed.

On August 6th. the small 300 ton Mamuta set out to sail from Port Moresby to Daru, her crew 32, and carrying 82 passengers of whom 27 were children. The next day, the Japanese Submarine RO-33 found her, closed to only 300 metres to unleash a barrage of gunfire, in minutes the small ship was a wreck, killing many on board, only 28 survived. It was a vicious attack causing unnecessary loss of life.

August 29th. found the freighter Malaita escorted out of Port Moresby by the Tribal Destroyer HMAS Arunta, commanded by Commander J. C. Morrow RAN (my Executive Officer in HMAS Shropshire later in the war) Malaita picked up a torpedo from RO-33, but was towed to safety. Arunta went after the Japanese Submarine, picked her up on her ASDIC, and proceeded to despatch her with all hands, at least the violent attack on the vulnerable Mamuta was now avenged.

The Year of 1943.

On February 19th. 1943, another flight by the floatplane from I-21 was made over Sydney, this time she was sighted, AA guns opened fire, but missed, there was no important shipping present, and the Glen flew back to her Submarine to be recovered.

Between Mallacoota in the South and Bundaberg in the north, these ships were sunk in 1943 by enemy submarines.

Kalingo, on January 18th. by I-21.

Iron King, on February 8th. by I-21.

Starr King, on February 10th. by I-21.

Recina, on April 11th. by I-26.

Kowarra, on April 24th. by I-26.

Limerick, on April 26th, by I-177.

Lydia M. Childs, on April 27th. by I-178.

Wollongbar, on April 29th. by I-180.

Fingal, on May 5th, by I-180.

The Australian Hospital Ship Centaur, on May 14th. by I-177.

Portmar, on June 16th, by I-178. The last victim to fall to Japanese Submarines.

By mid-June in 1943, the IJN had abandoned submarine operations off the Australian East coast.

Operations off Western Australia.

I-165 had one brief and uneventful patrol off NW Australia and thus ended all Japanese submarine activity in Australian waters.

One last hurrah by German U-boat U-862.

On December 9th. 1944, the German U-Boat U-862, left Jakarta bound for Germany, but decided to sortie into Australian waters, she shelled the Greek tanker Ilissos, 130 miles SE off Adelaide, and the U-Boat went on to sink the Liberty ship Robert J. Walker on Christmas day, 85 miles south of Jervis Bay.

Then at last homeward bound, Peter Sylvester was sunk SW of Fremantle, the very last ship to be sunk on the Australian Station.

Conclusion.

Over 30 months, 27 Japanese Submarines had been busy in Australian waters, their main thrust over 12 months between June 1942 and June 1943.

18 ships, of 86,600 tons were sunk off our east coast, and the small Mamutu in northern latitudes, another 25 ships had suffered some damage when attacked, but still survived.

467 had died, and that figure includes those killed when HMAS Kuttabul was destroyed during the Midget attack in 1942.

At last the danger from enemy Submarines operating around our coastline was finally over, but it had been a bumpy ride.

Bibliography.

Blair, C. Silent Victory. The US Submarine War against Japan. Bantam Books, New York, 1976.

Dull, P. S. A Battle History of the Japanese Navy. United States Naval Institute. Annapolis. 1978.

Gill, G. H. Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945. The Australian War Memorial. Canberra. 1968.

Gregory, M. J. Under Water Warfare. The Struggle Against the Submarine Menace. 1939-1945. The Naval Historical Society of Australia Inc. Garden Island. NSW. Reprinted 2002.

—————— Midshipman’s Journal September 1939- February 1941.

Hashimoto, M. Sunk, The Story of the Japanese Submarine Fleet. Cassell and Company. London. 1954.

Howarth, S. Morning Glory. A History of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Arrow Books. London. 1985.

Jenkins, D. Battle Surface. Japan’s Submarine War Against Australia 1942-1944. Random House. Milson’s Point, NSW. 1992.

Milligan, C. S. Australian Hospital Ship Centaur, The Myth of Immunity. Nairama Publications. Hendra Queensland. 1993.

Watts, A. J. & Gordon, B. G. The Imperial Japanese Navy. McDonald. London. 1971.

Contact Mackenzie Gregory about this article.