By June 1918, the Allies had halted the German spring offensive in the Somme Valley some 20km east of the vital logistics centre of Amiens.

Ursula Davidson Library call number 572 FITZ 2018

The Germans, however, could still observe the city from the heights of Wolfsberg, which was protected by a salient in the new Western Front extending west some 2km around the fortified village of Le Hamel.

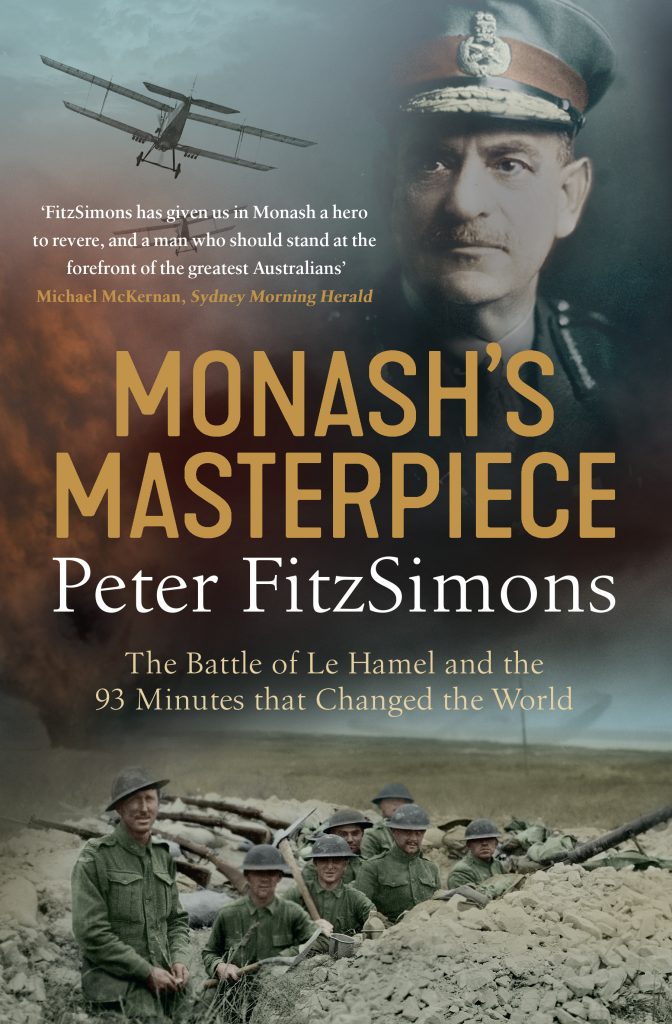

Monash’s Masterpiece describes the battle of Le Hamel on 4 July 1918, which was a meticulously planned, all-arms deliberate attack by the recentlyformed Australian Corps. The attack had a limited objective – to eliminate the salient around Le Hamel and capture Wolfsberg. Beginning at first light, it was planned to take 90 minutes and, in the event, it secured its final objective in 93 minutes.

Peter FitzSimons, AM, is the author or joint author of some 35 military and other histories. A journalist, he writes in an informal manner in the present tense, constructing his story like a novel. This appeals to many readers, but offends some historians. Nevertheless, he is supported by an excellent team of researchers; and the 1000-odd endnotes, the bibliography and the 16 welldrawn maps, attest to the quality of the underpinning research.

Removing the Hamel/Wolfsberg salient was an obvious step for the Allies once the new Western Front had formed. The trick would be how to do it without excessive loss of life, at least on the Allied side. By this stage of the War, reinforcements from Australia had virtually dried up.

Enter Australia’s new corps commander, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash. Monash was a citizen-soldier – a brilliant, innovative engineer, who had devoted his spare time to service in the pre-war militia. A brigade commander on Gallipoli in 1915, he commanded the 3rd Australian Division at Messines and Third Ypres in 1917 and on the Somme during the 1918 German spring offensive. He had developed a reputation for clarity of thought and attention to detail which was far superior to that of his contemporaries. Favoured by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig and King George V, he was appointed to command the Australian Corps in May 1918.

Monash was keen for the Australian Corps to return to the offensive, so developed a plan to capture Hamel/ Wolfsberg with minimal casualties. His idea was to employ tanks, artillery and aircraft to get the infantry onto the objective with minimal fighting, and then for the infantry to mop up and hold the ground gained. The keys would be secrecy, detailed planning and co-ordination, excellent logistics support (including by tanks and aircraft), inter-arms training, several rehearsals, and, finally, exhaustive planning conferences to tie up loose ends.

The battle itself involved 11 battalions of Australian infantry, four companies of American infantry, some 55 tanks of the Royal Tank Corps, several squadrons of the Australian Flying Corps and the Royal Air Force, and the massed artillery of the British Fourth Army. It did not all go to plan – some tanks got lost in the dark at key points (Pear Trench, Kidney Trench); enemy resistance at several points could only be overcome with great courage by the infantry; and a German counter-attack on Wolfsberg was partially successful before it was again repelled by a counter counter-attack. Despite the setbacks, the overall achievement was remarkable and the staff-work would become the model on which the subsequent final 100-days offensive would be based.

Of course, it does not need 414 pages to tell the story of Le Hamel. Colonel John Hughes-Wilson, a past president of the International Guild of Battlefield Guides, does so perfectly adequately in 163 pages in his book, Hamel 4th July 1918: the Australian & American victory [Unicorn Publishing Group: London; 2018] – see my review in United Service 69 (4), 29, December 2018.

FitzSimons, however, uses the additional space to detail the context, the lead up to the battle, the battle itself, the aftermath, and the later fate of some of the key players around whom he has built his story. In doing so, he interleaves discussion of the political machinations of generals, politicians and journalists, and activities from higher command right down to section level, at times on

the German side as well, examining the battle as it evolved from the left flank of the assault across to the right flank and then back again. If you can afford the time, then reading FitzSimons’ book is well worth the effort.

There is, however, one disconcerting error. At p. 364, FitzSimons asserts that “… Bean is very positive about General Ivan Mackay, who presided over the slaughter at Fromelles”, but cites no literature to support the claim. Rather than Lieutenant-General Sir Iven Mackay, who rose to general rank in World War II, I suspect FitzSimons intended to refer to Major-General the Hon. J. W. McCay, who commanded the 5th Australian Division during the battle of Fromelles on 19-20 July 1916. This blemish notwithstanding, I highly commend the book to all readers.

Reviewed fro RUSIV by David Leece, United Service 71 (1) March 2020

Contact Royal United Services Institute about this article.