The village of Kagi nestled high in the mountains half-way along the Kokoda Track is home to a devout community of Seventh-Day Adventists and subsistence farmers. Until Christmas Eve 2017, Kagi was also home to a national hero of both PNG and Australia. Havala Laula was one of the last living links to a very special generation of Papua New Guineans. A generation whom 75 years ago toiled over the Kokoda Track transporting the much-needed supplies of food and ammunition before carrying wounded Australian soldiers to safety. With Havala’s passing it is time for both Australia and PNG to revisit how we recognise and remember men like Havala and the legacy they leave behind.

Many readers would be familiar with the famous Bert Beros poem “The Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels” that painted a picture of gentle, loyal and devoted Papuan carriers. People that put aside their own needs to faithfully carry out their duty of carrying wounded Australian soldiers home to safety. The poem reads in part;

Slow and careful in the bad places

on the awful mountain track

The look upon their faces

would make you think Christ was black.

**

Many a lad will see his mother

and husbands see their wives

Just because the fuzzy wuzzy

carried them to save their lives.

Sapper Beros was a member of the 7th Division Engineers who had seen first-hand the effort made by the carriers. In October 1942 when his poem first appeared in the Brisbane’s Courier Mail, the Australian public were already becoming aware of the contribution made by the people of Papua. A month prior, Cinesound Productions Ltd released the newsreel, Kokoda Front Line.

Damien Parer’s Oscar-winning work not only brought home to Australians the realities of the war in the Pacific but also images of natives carrying injured Australian soldiers.

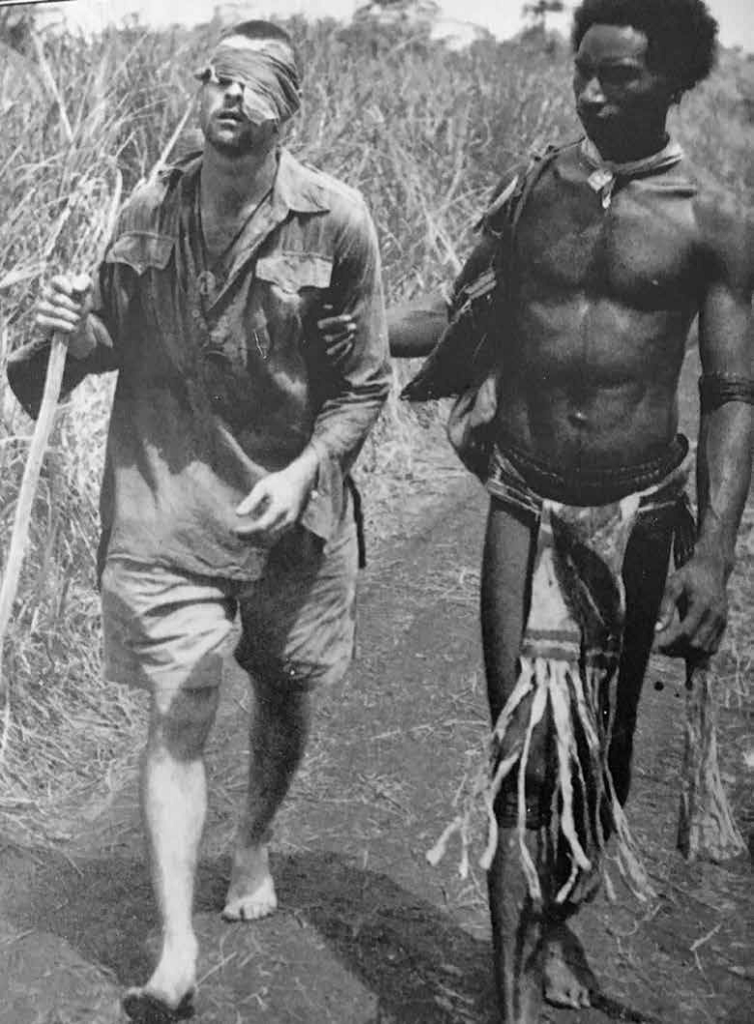

A few months after both the newsreel and poem were released, the famous George Silk photograph of the Papuan carrier, Raphael Oimbari, escorting the injured Australian soldier George ‘Dick’ Whittington along the Buna road, appeared in Brisbane’s Courier Mail. The Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel was becoming immortalised by the Australian public.

However, mythology often focuses on the triumphs and leaves out the unpleasantries. In the narration of Parer’s newsreel he states; “the black-skinned boys are white”, so too in Bero’s poem similar words conjure up an image of equality; “…make you think Christ was black”. The attempt to raise the status of the Papuan carrier to be equal with that of an Australian soldier was an idealistic one. Not during the war, nor in the following post-war years did the Papuan carrier receive the same pay, conditions or recognition as his Australian counterpart.

The Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel legend was founded on a master-servant relationship. Papua in 1942 was an Australian territory, in February of that year, civil administration had given way to martial law. European men that were deemed not essential to the war effort, along with European women and children, were repatriated back to mainland Australia. By April 1942 the Australian New Guinea Administration Unit (ANGAU) was created. Although ANGAU had in their charter to look after the welfare of the local populace, the reality was the people of Papua had no option but to stay in their villages.

By June of 1942 the New Guinea Force Commander, Major General Basil Morris gave orders on how native labour for the war effort was to be contracted. Morris issued the Employment of Natives Order which stated that Papuans could be contracted for up to three years, during which time they were not to be absent without leave, desert or refuse to carry out their duty. If any carrier broke any of the rules of the order they were often dealt with quite harshly by their administrators. Punishment ranged from loss of privileges such as pay or tobacco to more harsher penalties such as being drilled with a heavy pack on, gaol or in some cases flogging. Of course if any carrier was seen to be aiding the Japanese they could be executed.

As the war on the Kokoda Track intensified so too did the need for more carriers. Often false promises such as better conditions and shorter contracts were used to recruit carriers. Between August and December 1942 over 16,000 Papuans were employed by ANGAU, many of whom would work on the Kokoda Track. Whilst some came from the villages that were high in the Owen Stanley Ranges, most came from the low-lying townships and costal settlements. The cold mountain climate especially at night, along with poor rations and sleeping gear did not offer much in the way of comfort. ANGAU officer, Captain “Doc” Vernon, a veteran of the First World War who gave medical attention to soldiers and carriers alike, noted in his diary;

“Every evening scores of our carriers came in, slung their loads down, and lay exhausted on the ground; the immediate prospect before them was grim, a meal that only consisted of rice and none too much of that and a night of discomfort and shivering as there were only enough blankets to issue one to every two men…”

Sickness of the carriers was of major concern. As mentioned many were not used to the colder climate of the mountains in the Owen Stanley Ranges, pneumonia was rife. War correspondent Osmar White wrote in his book Green Armor; –

“About six pneumonia cases came back every time a carrier line went into the mountains. The carriers were mostly coast boys acclimatised to heat and humidity. After a couple of crossings, the sharp cold of the mountains, the poor food, and the labour of lugging loads over the passes broke them”.

If the food, medical support and sleeping conditions were not bad enough, the work of the carriers was back-breaking. The Kokoda story is full of accounts of the heavy packs carried by the Australian soldiers, but little attention is given to the weight that carriers had to bear. The carriers not only had to deal with carrying their allotted equipment of ammunition, rations and medical supplies for the troops, they had to carry their own food. Bert Kienzle, like Vernon, entered service with ANGAU. Kienzle a man who knew the Territory and the people well, became instrumental in organising the carrier lines. Kienzle noted in his diary; –

“A carrier carrying only foodstuffs consumes his load in 13 days and if he carries food supplies for a soldier it means 6 ½ days supply for both soldier and carrier. This does not allow for the porterage of arms, ammunition, equipment, medical stores, ordnance, mail and dozens of other items needed to wage war, on the backs of men”.

The impact was not just on the carriers themselves, the war was indiscriminate. As Japanese and Australian troops moved through villages, they trampled crops, destroyed huts, and took precious food from the gardens. Terrified villagers fled into the jungle desperately trying to escape the fighting or take cover from air-raids. In the process, villages were destroyed and an uncounted number of villagers were killed, injured or mistreated. For those communities that were not in the path of the fighting, they still had the effect of having their husbands, brothers and sons away from the village. With no men to work the gardens or do the heavy lifting around the village, the impact was detrimental to their well-being. In retrospect the Papuans had little reason to be loyal to their “Taubada” or white masters, who often treated them as second-class citizens in their own land. It is understandable that some carriers deserted and returned to their villages and families.

When the carriers made their journey over the Kokoda Track with their load of military supplies, they turned around and carried out the wounded Australian soldiers. This is the part that the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel legend plays up to and rightfully so. There is not one report of any Australian soldier being abandoned by the Papuan carriers, not even during heavy combat. They will always have the eternal gratitude of the Australian soldiers and their families for whom their survival depended on. Many Australian veterans to this day look back with immense gratitude for the help received.

In February of 2017, Havala, thought to be the last known Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel living along the Kokoda Track, visited Melbourne. During his visit he met several veterans of the 39th Battalion including Alan ‘Kanga’ Moore. The meeting was an emotional one, two old warriors together for one last time. Although the language barrier between the two men made it hard to communicate with words, a simple embrace and the expression on both men’s faces conveyed the great admiration both had for one another. When a reporter from the Australian Broadcasting Commission asked Kanga if the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels had received enough recognition for their work during the war, Kanga replied;

How was the service of the carriers recognised after the war? As the fighting in the Owen Stanley Ranges concluded and only two weeks after Kokoda had been reoccupied, a banquet and presentation to the carriers was held at Kokoda by the Australian Army. Lieutenant Bert Kienzle had requested stores of yams, taro, tobacco and calico along with extra rations for a ‘feast’. Kienzle also sought permission for the carriers to have “1 days rest”.

Major J. H. Jones from ANGAU sent a memo stating; “…it has been decided to award medals to natives who have performed brave or gallant acts”. The memo also requested that Field Staff nominate the names of worthy recipients. Men like Kienzle put names forward and a small percentage received a medal. One side of the medal had the Australian Coat of Arms and the other the words; ‘For Loyal Service’. However, the fighting at the northern beachheads was still to come and many Australian service personnel believe the small recognition given by the army was a strategic move to encourage existing carriers to continue working.

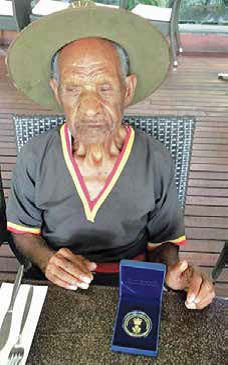

Calls to give financial support to all carriers in Papua New Guinea who contributed to the war effort were promoted as early as 1943. In the Sydney publication Pacific Islands Monthly it was proposed that an annual Christmas payment of £10 be made to all carriers until their death. This idea never eventuated and it would be four decades before any money was forthcoming. In the 1980s the Australian Government gave 3.25 million dollars to the PNG Government. Some payments of K1,000 (approx. $500 AUD) were made to individual carriers. The most famous Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel, Raphael Oimbari, received a one-off payment of K2,000 and was recognised with the Order of the British Empire in 1993. However, for many carriers no payment eventuated. Too little too late in any case as many carriers had by then passed away.

As for remembrance perhaps the most significant gesture was not done by either government rather by an individual. In 1959, Bert Kienzle, who returned to his residence near Kokoda after the war, built a memorial at the Kokoda Plateau recognising the contribution of the carriers. Kienzle had hoped that the design in the centre piece would be struck as a medallion and given to surviving carriers, especially those that had not received the Loyal Service Medal.

The idea of a medallion seemed to fizzle out and it would not be until 2009-2011 that the Australian Government issued medallions. Only 68 surviving carriers n the whole of PNG received a medallion. Around this time, the Australian Minister of Veteran Affairs, Hon. Alan Griffin MP stated;

“…there were no plans to make payments to surviving Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels instead the focus was on providing aid and support towards improving the capacity of the communities that many of these people came from”;..

Eitherway it was too little too late to help the actual carriers themselves. At the 2017 Anzac Day Dawn Service at Bomana War Cemetery in Port Moresby, Havala was in attendance. So too was the Australian Governor General, The Hon. General Sir Peter John Cosgrove, AK, MC. The service marked not only Anzac Day but the 75th Anniversary of the Kokoda Campaign. Sir Peter took Havala by the hand and the two of them laid a wreath at the cenotaph. Sir Peter later presented Havala with the Governor General’s medallion.

For all the countless other Papuan New Guineans that helped Australia during the war, their individual recognition went unrecognised. Now with the passing of last of Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels such as Havala, we have lost that living conenction. All we can do now is honour their memory by never forgetting their service and sacrifice. PNG and Australian school children should be encouraged to find out not just the real story behind the legend but also to seek out the personal stories of these impromtu angels.

Contact David Howell about this article.