Introduction

1888 was a particularly busy year in the life of the nascent Militia forces in Victoria. Formed in 1885 to replace in large part Volunteer forces which had been in existence since the mid- 1850s, Militia involvement in the social, civil and military life of this wealthy colony was already comprehensive and well reported.

In 1888, in addition to the traditional four day Easter camp, the Review on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s birthday, engagement in the Victorian Rifle Association matches and acting as guards and escorts for such duties as the opening of Victoria’s Parliament, the Militia also became involved in the major Centenary Exhibition of 1888. All of this on top of individual unit training, and social events for the small permanent staff and Militia officers. In November of each year, on the occasion of the Prince of Wales’ birthday, a complex one day training exercise was also held to test in a ‘sham fight’ the operational skills and leadership of units and officers alike. In November 1888, the exercise was centred on the village of Oakleigh, established in 1853 and located 19 km to the south-east of Melbourne City.

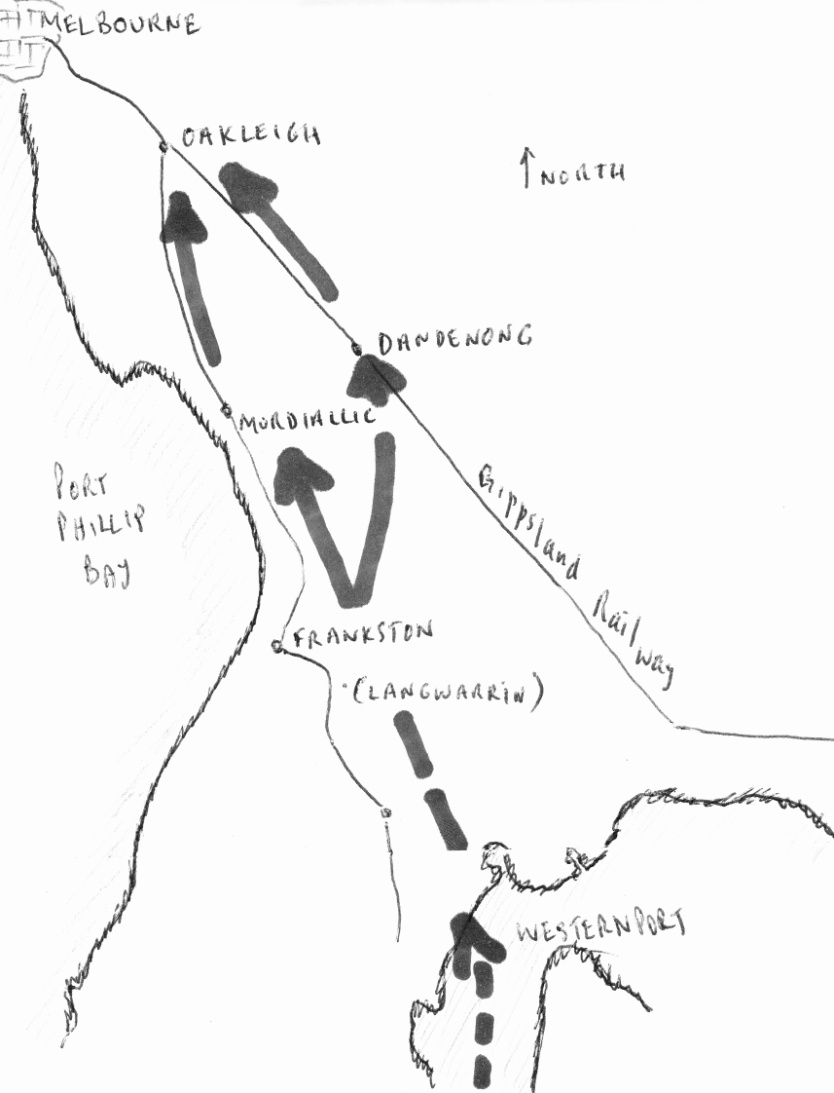

This article focuses on that Oakleigh exercise. Some context is needed to understand why an exercise would even be held in this area. The annual Easter training camps had recently begun to be held at the newly established training ground at Langwarrin on the Mornington Peninsula 96 km south east of Melbourne. Langwarrin would, rather self-consciously, become known in time as ‘Australia’s Aldershot’. From the early 1860s when Victoria’s Volunteer forces were themselves new there had been concerns that an ‘invader’ – at different times imagined to be French or Russian – could attack Melbourne overland from Western Port. By 1888, as the fortifications at the ‘Heads’ of Port Philip Bay continued to strengthen, an attack through the Heads became more problematical for any invader and a theoretical overland approach to Melbourne became a practical alternative to attacking through the forts at the Heads. It was partly in response to this thinking that Langwarrin, squarely positioned between Western Port and the Dandenong track access to the inner approaches to Melbourne, gained prominence as a training ground from 1887 when encampments were first held there.[1]

So it became a regular occurrence for the smaller one day exercise in November of each year to be held on ground over which a potential enemy, if it took that route to Melbourne, might be expected to traverse. In 1887 the exercise was held on the approaches to Melbourne along the coastal track near the Port Philip bay-side town of Brighton. In June 1888 it seemed like the real thing was going to happen when the telegraph lines to Europe were suddenly and inexplicably cut off – rumours of war in Europe flew about, fanned by local media. The Victorian Navy and garrison forts stood to their posts and the Militia was alerted.[2] When the reason for the cables being cut – volcanic activity in the Netherlands East Indies – became known, the alert subsided. Nonetheless, the false alarm added spice to the November exercise planned for 1888.

The ‘battlefield’

The exercise was held over ground leading from Dandenong through Spring Vale to the railway and road junction at Oakleigh village south-east of Melbourne.[3] While Oakleigh’s railway did connect Melbourne city with the Gippsland farming districts of eastern Victoria (the Gippsland railway through Dandenong terminated at Oakleigh), perhaps as important was its road junction providing access to Melbourne from Dandenong. Here the so-called ‘three-chain road’ provided a route from Dandenong which avoided the swampier, lower lying tracks closer to Port Philip Bay. From a training point of view, the country between Oakleigh and Dandenong was close to ideal. Sparsely settled, it was undulating and lightly timbered.

Oakleigh village itself and its principal businesses – such as they were – was aligned along ‘the Broadwood’, a small ‘straight’ section of Dandenong road between the track later known as Warrigal Road and the start of Fern Tree Gully Road. Kerosene lamps illuminated at night. With the opening of the railway not long before, land around Oakleigh was just starting to be developed in the urban sense, but was not yet settled around the railway station with its wooden building with station master living rooms, a waiting room and ticket office, completed in 1881. In fact around the period of the militia exercise, no less than seven estates were put up for sale. But Oakleigh remained very much a rural setting albeit important as a ‘grand junction’ of road and rail. [4]

![Oakleigh Railway Station c1880s [5]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK2.jpg)

The Forces

A quick overview of the Militia and Volunteer forces in Victoria in 1888 will set the scene. Barely three years old, the new Militia forces – formed in a major reorganisation of the Victorian Defence Forces from 1884 – were still developing. The old Volunteer infantry, artillery and cavalry had largely been replaced by paid but part-time Militia forces which included a leavening of former Volunteer officers and men who carried forward their experience of part-time or actual soldiering as former British Army veterans. They were supported by a small professional staff of permanent officers and non-commissioned officers who were mostly ex-British Army or seconded from the British Army. This included the commander of the Victorian Forces, Colonel Henry Studholme Brownrigg, [8] and a number of key staff officers.

![Colonel H S Brownrigg 1888 [9]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK3.png)

![Colonial Auxiliary Long Service Medal & Volunteer Long Service Medal [10]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK4.jpg)

The ground force structure of the Victorian Militia and Volunteers in 1888 consisted of the following:

- Infantry – two metropolitan battalions as well as country battalions based on Bendigo, Castlemaine and Ballarat

- Field Artillery – both field gun batteries and horse artillery with Nordenfelt quick firing guns.

- Garrison Artillery, which consisted of fixed coastal guns in various fortifications from Warrnambool to Queenscliff to Fort Nepean on the eastern side of the heads.

- Mounted Rifles, detachments of which were volunteers mostly drawn from rifle clubs and mainly located in country districts

- Engineers – included men who could work communications equipment, explosives and mines as well as build fortifications and earthworks

- Supporting corps such as ambulance, commissariat and ordnance

- School Cadets – in several private and State schools in metropolitan Melbourne

- (civilian) Rifle Clubs – growing in prominence and influence, especially within the Victorian Rifle Association, and recognised by the new Defence Department as a potential defence asset.[11]

The 1888 exercise to defend Oakleigh Station involved the metropolitan infantry battalions, field artillery, and other sub-units and supporting services.

![Field Artillery [12]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK5.png)

![Victorian Infantry [13]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK6.jpg)

The advance guard of an attacking force (the ‘Red Force’) which had landed in Western Port Bay was advancing on Melbourne and aimed to capture Oakleigh village and railway junction.

The Red Force advance guard consisted of:

- ‘A’ and ‘B’ batteries of the Field Artillery Brigade each with six Armstrong 12 pdr. rifled breech loading guns under Major John Walter Hacker and Major John Richard Ballenger[14] The batteries arrived in Spring Vale – about half way between Oakleigh and Dandenong on the railway line – after a route march from Melbourne on 8th November and camped there that night.

![Major (later Colonel) J W Hacker[15]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK7.jpg)

![Major J R Ballenger 1888 [16]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK8.png)

- 1st and 2nd Battalions, Victorian Rifles, under the commands of Major Thomas Stephen Small and Major Robert Robertson[17] respectively, came to Spring Vale by train on the morning of 9th November along with the bulk of the Ambulance Corps[18]

![Colonel R Robertson[19]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK9.jpg)

Colonel R Robertson[19] ![Major R Robertson 1888 [20]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK10.png)

Major R Robertson 1888 [20]

The attacking force was placed under command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Montgomery Templeton, a member of the Victorian Council of Defence and Chairman of the Victorian Rifle Association.[21]

![Colonel J M Templeton [22]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK11.jpg)

![Red Force – Lieutenant-Colonel J M Templeton 1888 [23]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK12.png)

- A detachment of the Nordenfelt Battery under Captain Frederick Godfrey Hughes[24]

- A detachment of Victorian Artillery, acting as infantry under Captain William Robert Jefferson Christie[25]

- ‘C’ Battery Field Artillery under Captain Rupert Turner Havelock Clarke in the absence due to illness of Major Nicholas William Kelly [26]

- The Field and Telegraph Company of Engineers, Corps of Engineers under Captain Robert Lisle Straughan Amess [27]

- A detachment of Mounted Rifles under Captain William Braithwaite [28]

![Mounted Rifles [29]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK13.jpg)

- One battalion of Senior Cadets under Captain Douglas Lennox Henry. [30] A journalist from the Argus, covering the exercise, said that:

‘both in the matter of physique, promptness in movement and expertness in the use of their arms [the cadets] did no discredit to the militia, but did very much credit to the militia officers who have taken the movement in hand.’[31]

- The medical department was commanded by Surgeon-Major John Fulton, MD [32] with Surgeon-Major James Robertson MB, Surgeon-Major Charles Snodgrass Ryan, Surgeon Brown and Surgeon Henry Ogle Moore BA MB, of the Dandenong Mounted Rifles medical department [33] as his staff. There were several bearer parties working with the fighting line during the action, and a first dressing station for the defence was established at the rear, in a well selected position.[34]

![First Aid Dressing Station [35]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK14.jpg)

![Major-General Sir C S Ryan [36]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK15.jpg)

‘had two telephone lines about a mile long, reaching from the base of the defensive positions to its outposts by either flank, and fixed them with the Ader telephone, a new appliance, which was kept in operation all through the action with very good results.’ [37]

Blue Force was under command of Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Carodac (Tom) Price[38], with Major Ernest Frederick Rhodes of the Royal Engineers as his staff officer.[39]

![Colonel T C Price [40]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK16.png)

![Blue Force - Lieutenant-Colonel T C Price 1888 [41]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK17.png)

One man very likely to be there that day was John William Cordwell, a soldier in the 2nd Battalion, which had as its motto ‘For God and Country’. A carpenter and early trade unionist, he had emigrated from England in 1882, settled in Fitzroy, bought a small cottage and joined the Volunteers and then Militia. He was a keen rifleman and member of the Victorian Rifle Association, and with his company won a Brassey Field Firing medal in each of 1899 and 1901 competitions as well as being awarded for his service the Volunteer Long Service Medal and Colonial Auxiliary Long Service Medal. Colour Sergeant Cordwell did not see active service in the Boer War or WWI – perhaps because of his family responsibilities with five young children – but continued to serve until 1922, when was placed on the Retired List as an Honorary Lieutenant.[42] If Cordwell was representative of the men exercising on that day at Oakleigh, then the Militia were of a high standard indeed.

![Colour Sergeant J W Cordwell (standing, right) at Langwarrin 1906[43]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK18.jpg)

Click here for Part 2

[1] Calder, W., Australian Aldershot, Jimaringle Publications, 1987, p.9.

[2] See the Argus, 2nd July 1888, p7.

[3] Oakleigh’s permanent station buildings were not completed until 1891.

[4] Gobbi, H.G., Taking Its Place, Oakleigh & District Historical Society, Melbourne 2004, p63 & 67.

[5] Oakleigh & District Historical Society Inc. Collection.

[6] The Age 27 October 1888, p18 and the Argus 10 November 1888, p13.

[7] The Age 10 November 1888, p11. An hippodrome is a stadium, theatre or concert hall…

[8] For a biography of Brownrigg, see https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Dictionary_of_Australasian_Biography/Brownrigg,_Major_Henry_Studholme

[9] The Australasian, 7th April 1888, p741.

[10] Awarded to Colour-Sergeant J W Cordwell, a member of the 2nd Battalion – Cordwell Collection

[11] The infantry were armed with Martini-Henry rifles. Rifle Clubs – see Kilsby, A., The Riflemen, NRAA/Longueville Media, 2013.

[12] ‘Our Defenders’, drawn by George Rossi Ashton, c1890

[13] ‘West Melbourne Regiment 1890’ in Wedd, M., Australian Military Uniforms 1800-1892, Sydney 1984, p68.

[14] The Argus 10 November 1888, p13. Hacker – joined St Kilda Volunteer Artillery 1881, by 1900 Lieutenant-Colonel, Assistant Quarter-Master General and commander Victorian Railways Volunteer Regiment. English-born Hacker was an employee of the Melbourne & Hobson’s Bay Railway Company, then joined the Victorian Government Railways where he became the Chief Accountant – Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, p5. Ballenger – Volunteer Lieutenant Royal Victorian Regiment of Artillery 1876 rising to Lieutenant-Colonel by 1897 – VGG 52, 30 Apr 1897, p1749. A fireman and member of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade Board from 1892; a brewer for more than 20 years at Carlton & United Brewery, managed the Yorkshire Brewery at Abbotsford and was licensee of the Austral Hotel, in Melbourne. Later President of the Licenced Victuallers Association Victoria and a well-known yachtsman – Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, p69.

[15] Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, fp80.

[16] The Australasian, 7th April 1888, p741.

[17] Small – joined the Richmond Corps of Volunteer Rifles 1864, rose to Major in Militia in the 1st or West Melbourne Battalion, Victoria Rifles and finally as Lieutenant-Colonel 1890 – VGG entries 1860-1900. Robertson – joined the Volunteer Metropolitan Rifle Corps 1872; rose to Lieutenant-Colonel commanding the 1st Battalion Victorian Rifles and then to full Colonel commanding both the Militia Infantry Brigade and the 1st Battalion 1897 – VGG entries. English-born Robertson was one of the sons of the firm R. Robertson & Sons, manufacturing jewellers – Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, p5

[18] Established in 1886 – see VGG 87 13/8/1886 p2319 – with 1 x surgeon-major, 1 x sergeant-major, 1 x sergeant-compounder, 2 x sergeants, 3 x corporals, 32 privates; disbanded 1889 – see VGG 77 26/7/1889 p2552.

[19] Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, fp160.

[20] The Australasian, 7th April 1888, p741.

[21] The Age, 10 November 1888, p11. Scottish-born Templeton founded the National Mutual Life Association of Australasia in 1869 and was president of it when he died in 1908. He joined the Volunteers in 1864, was a member of the Victorian Council of Defence1883-1897 and Chairman of the Victorian Rifle Association from 1882 to 1905, during which time he led the Victorian Rifle Team to Bisley in 1897 which won the Kolopore Cup – biography in Kilsby, A., The Bisley Boys, Melbourne 2008, p104.

[22] Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, fp192.

[23] The Australasian, 7th April 1888, p741.

[24] A three gun section of a Nordenfelt battery was based at Sunbury in connection with the Victorian Cavalry. See VGG 2 2/1/11885 p99 and Cox, L.C., The Galloping Guns, Coonan’s Hill Press, 1986,pp2-32. Hughes – joined the St Kilda Corps of Royal Victorian Regiment of Artillery 1883; was Captain of the Nordenfelt Battery of the Field Artillery Brigade 1888, Major in the Victorian Horse Artillery 1891; and rose to Lieutenant-Colonel and Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General of the Victorian Militia Forces by 1900 – VGG entries. See The Galloping Guns p23&p31; and http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hughes-frederic-godfrey-7077. Hughes later commanded the 3rd Light Horse brigade in Gallipoli during WWI, retiring as a Major-General.

[25] Christie – Joined 2nd Brigade Garrison Artillery Belfast Battery in 1885 – VGG 19 p620 20/2/1885; Volunteer Captain 1886; reverted to Militia Lieutenant 1888; resigned 1895 – VGG entries

[26] The Argus 10 November 1888, p13. For a biography of Kelly, later wounded in the Boer War, see Kilsby, A., The Bisley Boys, Melbourne 2008, pp85-86. Clarke – Lieutenant on probation 1885; unattached list 1886; from reserve to Victorian Horse Artillery 1889 – VGG entries. See http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/clarke-sir-rupert-turner-5672/text9581, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed online 18 March 2017.

[27] The Corps of Engineers was formed in 1884 – see VGG 7 19/1/1884, p151. Amess – Lieutenant in the Volunteers 1880; Engineers 1882 but retired as Captain 1891 – VGG entries. The Amess family owned Churchill Island from 1872 to 1929. R.L.S. Amess was a son of the original Samuel Amess; Samuel Amess was one of Melbourne society who entertained the Shenandoah officers and crew when in Melbourne in January 1865. He claimed the Churchill Island cannon came from the Shenandoah. https://victoriancollections.net.au/items/55b1c89d2162f11848cfd356

[28] Most likely from the Ferntree Gully detachment (no detachment at Dandenong). Braithwaite – originally with Preston Volunteers 1885; Preston Mounted Rifles 1887; rose to Lieutenant-Colonel in the Victorian Mounted Rifles but was retired in 1903 following a ‘command dispute’ with the new Australian Military Commander Major-General E T H Hutton – VGG entries and Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, p50. Obituary in Weekly Times, 12th August 1922, p6. English-born Braithwaite was a master tanner and currier, owning a tannery in Preston area.

[29] At VRA Matches November 1888, unknown newspaper.

[30] It was the first time that senior cadets had worked with the Militia in an exercise of this sort. It is not known from which schools the battalion was drawn. A Volunteer Cadet Corps was formed at Dandenong State School 1403 in 1885 – VGG 79 21/8/1885, p2327. Another was formed at Oakleigh State School in 1886 1601 VGG 76 9/7/1886 p1967. Henry – Joined the Militia in 1884 and became Staff Officer Victorian Volunteer Cadet Corps in 1886; rising to Lieutenant-Colonel in 1897 commanding cadets through 1900 – VGG entries.

[31] The Argus 10 November 1888, p13.

[32] Fulton – the principal medical officer and infantry brigade surgeon – see VGG 63 3/7/1885, p1879

[33] MD – Doctor of Medicine; MB – Bachelor of Medicine. Moore – appointed surgeon VGG 47 16/4/1886, p1022. The Dandenong Rifle Club formed 1888 – VGG109 23/11/1888 p3489. Robertson, Brown – unidentified. Ryan – later Major-General Sir Charles Snodgrass Ryan who joined the Victorian Volunteer Medical Service in 1878 and served in WWI. He was known as ‘Plevna Ryan’ because he had served with the Turkish forces in the Russo-Turkish War 1877-78 – Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, pp48, 60.

[34] The Age 10 November 1888, p11.

[35] Unknown newspaper c1894.

[36] Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, fp160.

[37] The Age 10 November 1888, p11. About the Ader Telephone see http://telephonecollecting.org/articles/berthon.html – ‘The Berthon-Ader Wall Telephone’; Reprinted from the issue of ATCS newsletter, May 1988. See also http://www.telephonecollecting.org/Bobs%20phones/Pages/Essays/Ader/Ader.htm.

[38] The Age 27 October 1888, p18. Price – commanded the Victorian Mounted Rifles and had been appointed to command the Victorian Rifle Volunteers (later called the Victorian Rangers) – see VGG38 27/4/1888, p1191. Tasmanian-born Price, a former British Army officer who had retired to Victoria, would later take a contingent of Mounted Rifles to South Africa during the Boer War. He was later Commandant of Queensland – see http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/price-thomas-caradoc-8110

[39] Rhodes (1852-1901) – commander of the Engineers in Victoria – see VGG 63 3/7/1885 p.1879. He had joined the RE as a lieutenant in 1872 and in 1884, was seconded to Victoria. He was a brother of Cecil John Rhodes, mining magnate and imperialist of Africa fame.

[40] Colonel Tom Price in Calder, W., Heroes and Gentlemen, Jimaringle Publications, Canterbury, Victoria, 1985.

[41] The Australasian, 7th April 1888, p741.

[42] Kilsby, A., ‘John William Cordwell (1861-1936) – militiaman, carpenter’, 18 October 2016, commissioned biography.

[43] ‘Easter Camp, Langwarrin 1906’, courtesy J Cordwell Collection.

Contact Andrew Kilsby about this article.