As the 50th anniversary of the most severe domestic disaster to impact Australia approaches at the end of 2024, many are puzzled as to why the armed forces members who saved Darwin after Cyclone Tracy were not rewarded with a medal.

Decades after the event, the National Emergency Medal, established in 2011, has been recently rightly given to ADF members, and indeed many civilians who worked through cyclones, bushfires, and floods, now going back to 2009.[1] But those who gave their all after the cyclone that killed 71 Australians may not see the anniversary with more than private pride. Yet this was the biggest operation the armed forces of the country ever mounted outside warfare. It was not only in numbers of personnel – around 8,000 – who worked in the northern capital, but in time too: deployments were in months, and the hours put in were often 12 or more per day, especially in the early weeks; and the conditions endured in a tropical monsoon season were often appalling.

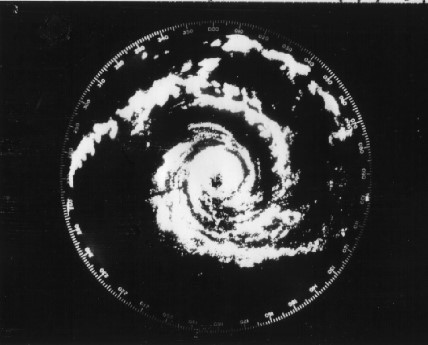

The cyclone that neared Darwin in the week before Christmas 1974 was small but gathering intensity as it approached. The diameter of its gale force winds was only about 100 km, in contrast to some north Pacific typhoons, which have had diameters of 1,500 kilometres.[2]

The capital of the Northern Territory was a big sprawling town, centred around its huge airport, with Australia’s longest runway. In January 1974 the Darwin population had been counted as 46,656.[3] Darwin was no stranger to destruction: it had been heavily damaged in cyclones in 1897 and 1937, and bombed by Japanese forces 77 times in World War II.[4]

The cyclone had been named on 21 December, but there was little notice of it taken as the local residents busied themselves with Christmas preparations. The first warning that Darwin itself was threatened came at 12.30 pm on 24 December, approximately 12 hours before the onset of destructive winds. [5] By the early evening it was apparent the cyclone would impact Darwin, although whether it would pass directly over the built-up area was not that clear. In the event it did, with a recorded surface wind speed of 217 km/h. [6] The eye of the storm crossed in the early hours of Christmas Day, and it was not until mid-morning the winds had died down. By the time the residents emerged from their places of shelter it was apparent massive damage had been done.

In fact, the comparison to the atomic blasts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in WWII were used frequently in the days ahead. The destruction was enormous. Between 50 and 60 per cent of houses were damaged beyond repair and in some of the northern suburbs the destruction was nearly 100 per cent.[7] It left more than 25,000 out of the 47,000 inhabitants of the city homeless and required the immediate evacuation of over 30,000 people.[8]

Between 26 and 31 December, a total of 35,362 people were evacuated from Darwin. Of those, 25,628 were evacuated by air, the remainder by road. [9]

Sixteen people died at sea, where according to the harbourmaster’s report: “At least 29 vessels were sunk or wrecked”. These included several of the large prawn trawlers that were based in the port, and a passenger ferry, the Darwin Princess. The biggest vessel to be sunk was the 120 foot three-masted steel schooner Booya, missing with five people on board. The Navy lost a patrol boat, HMAS Arrow, with the loss of two lives. In a double blow, the senior Navy officer present, Eric Johnston, noted a special tragedy:

To add to the Navy’s losses, four dependents, two wives and two children were also killed in their married quarters while their husbands were at their place of duty, and thus the Navy in Darwin with some 1.5 per cent of the population suffered 12 per cent of the total fatal casualties and indeed was the only service to so suffer. [10]

The Royal Australian Air Force immediately started bringing in essential supplies. Hercules aircraft flew in 7,000 blankets, 6,000 lbs of milk and 2,000 lbs of Red Cross medical supplies. While the run of supplies north was enormous, the evacuations were equally as large. On Boxing Day, the RAAF flew out 680 persons, and the following day 1,218 in 22 sorties. [11] The flights continued for many days, but meanwhile more RAAF members were flying in. Around 3,000 Air Force members were posted to Darwin for a three month period. [12]

A number of Navy vessels were quickly deployed from southern ports to Darwin. Sailors and officers were recalled from Christmas leave; ships were made hurriedly but thoroughly ready for sea, and soon a steady stream of warships were deploying north. At 2000 on Christmas Day Clearance Diving Team One was recalled from leave, with a special role envisaged of saving sinking vessels from foundering, and searching for trapped seamen or bodies. By 1000 the next day they were flying to the stricken northern capital. The destroyer Brisbane was the first to enter Darwin harbour, followed by the survey ship Flinders. Also deployed were the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne, the destroyer escort Stuart; tender Stalwart; fleet oiler Supply, destroyers Hobart and Vendetta, and the five landing craft Balikpapan, Betano, Tarakan, Brunei and Wewak. Thirteen ships, eleven naval aircraft and some 3,000 personnel were eventually involved. [13]

The Director General of the National Disasters Organisation, Major General AB Stretton, DSO, arrived in Darwin on 26 December with his staff officers to establish an Emergency Services Organisation Committee. Captain EE Johnston, the Naval Officer Commanding the North Australia Area, was appointed to the committee as Port Controller, with responsibility for controlling the port and its approaches, and for drafting an Emergency Plan in the event of a further cyclone. [14]

As preparations were made for the arrival of the naval task group, Captain Johnston relocated the naval headquarters to his residence, Admiralty House. It was agreed that the RAN relief force would be allocated responsibility for clearing and restoring 4,740 houses in the northern suburbs of Nightcliff, Rapid Creek and Casuarina. HS 748 aircraft continued to ferry personnel and stores north to Darwin and on the return trip taking evacuees south. Evacuees were accommodated in naval shore bases HMAS Kuttabul, HMAS Penguin and HMAS Watson in Sydney; and HMAS Moreton in Brisbane.

Meanwhile Clearance Diving Team 1 was surveying damage to the patrol boats and civilian craft, searching for missing vessels, clearing Stokes and Fort Hill Wharves, and assessing how to extract the wreck of the Arrow. [15]

The work of the divers was especially difficult. Warrant Officer Larry Digney recalled: It is difficult to explain how dark the water was in Darwin Harbour at that time. If you closed your eyes tight and then covered your closed eyes with your hands you may be close to having the visibility we had. Everything we achieved was with the use of our other ten eyes, our fingers. Once we located something on the seabed it was extremely slow work to ascertain just what it was….We worked 12 hours on and 12 hours off for 22 days straight in conditions rarely encountered by divers. [16]

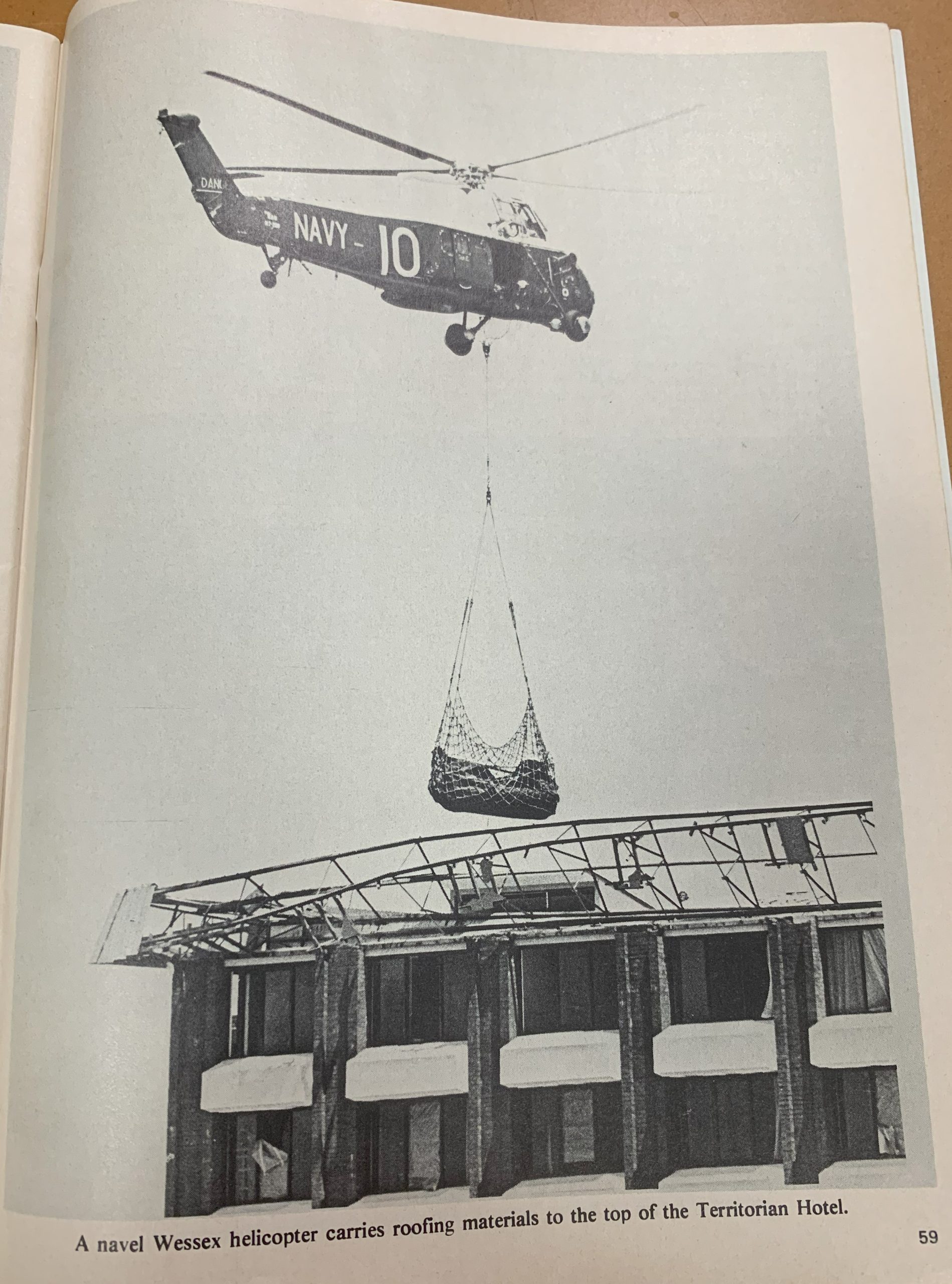

The raw statistics amply illustrate the magnitude of the relief work undertaken by the RAN. Between 1 and 30 January naval personnel spent 17,979 man days ashore, with up to 1,200 ashore at the peak of the operation. Working parties cleared some 1,593 housing blocks and cleaned up schools, government and commercial buildings and recreational facilities. They installed generators, rewired houses, repaired electrical and air-conditioning systems, re-roofed or weatherproofed buildings, and maintained and repaired vehicles. Some parties worked to save rare plants in the Botanical Gardens. Hygiene parties disposed of spoiled foodstuffs from houses, supermarkets and warehouses. Female personnel from Coonawarra supported civil relief organisations and manned communication centres. One enterprising sailor from Hobart filled in as a relief disc jockey for the local commercial radio station – essential not only for communication but for lifting morale in a shattered city. The Wessex helicopters transported 7,832 passengers, 110,912kg of freight and made 2,505 landings. The Navy’s HS748 aircraft completed 14 return flights to Darwin and carried 485 passengers and 22,680kg of freight. [17]

All of the relief work was carried out in the Wet Season of the Top End of Australia. This lasts from around September to April each year, and sees daily humidity generally over 90% with temperatures of over 30. Frequent and intense rain makes conditions even worse. Air-conditioning, used extensively now, was in its infancy in Darwin in 1974, and in any case there was massive power failure following the cyclone, often meaning buildings lacked even fans for some time.

The situation required creative thinking from all parts of the Armed Forces. Group Captain David Hitchins, the Commanding Officer of the RAAF base, described taking the initiative with spraying Darwin from the air to prevent disease: …the hygiene problem was extensive. Anyway, Sergeant Cowan went around and had a look and he came back and told me that if we didn’t do something fairly soon to prevent the menace of breeding flies and so on, we were going to be living in the middle of a very nasty situation….

[With] a little bit of sculling around, we found three old gentlemen, mostly old fellows about my age, who were agricultural pilots…We gave those blokes cart blanche to spray Darwin, including the RAAF Base. We said we’d provide them with a place to live, free beer, and they could control their own air operations.

Without pay, the three then “spent the next three or four days beating up and down the main streets of Darwin at about 100 feet” [18]

The pilots eventually did get paid, said Hitchins.

Some of the ways in which the Navy teams were able to help were different indeed. An officer later to become Chief of the Navy, Rear Admiral Shackleton, recalls being asked by a distraught woman to help find her husband’s pay envelope, which had been on the kitchen table when the cyclone struck. Such envelopes contained cash, as that was how people were usually paid then, rather than having their bank balance increased electronically. The only problem with helping the woman search was that her house had been largely destroyed. The Navy members swapped wry glances, but some of them volunteered, and the pay envelope was found.

Working parties were typically composed of 10 or 15 officers and sailors, depending upon the nature of the task. [19] Johnston noted:

Despite this, the cheerfulness and the work of the sailors and officers was a subject of much favourable comment. I mention officers for, apart from those controlling personnel, the officers were best employed in manual labour and a photo of the captain of Melbourne, Commodore Guy Griffiths, stripped to the waist and carrying a large baulk of timber, made the front pages in southern newspapers. [20]

At the end of January the Navy concluded operations and handed over to the Army. A Force Field Group of 650 personnel had been assembled and moved to Darwin, with a primary responsibility of individual home clearance; the repair of services, safety checks, and the re-roofing of homes. [21]

The Army effort put in was enormous. For example, during March 1975, the Force expended 9,376 man-days in house clearance and 1,419 man-days in assisting the civil authorities in other ways. Between 1 and 24 April, a total of 6,779 man-days was expended on house site clearance and 46 man-days in assisting the civil authorities. Total vehicle kilometres travelled during those periods were more than 58,000. [22] Later Governor-General Peter Cosgrove, then a captain, was one of the soldiers deployed. He later recalled: “I was up here in Darwin soon after Cyclone Tracy, when Santa didn’t make it into Darwin, so Santa didn’t but the Australian Defence Force did, we were here for weeks and weeks.”[23]

Lieutenant PA Pedersen recalled later: In most cases a team would arrive at a house which had been unroofed and whose interior was completely waterlogged. Plaster peeled from the walls. Debris – wall and window frames, smashed stairs and the like – was scattered throughout. Remains of the roof could often be found in the backyard.

The section commander would start by guiding his truck into the yard and clearing it. Strong winds were still blowing in Darwin and debris that could be flung about was quite dangerous. Indeed we were told that most of the cyclone casualties were injured in this manner. The team would then move inside and clean out the interior of the house. This could be a difficult task for a roof might be hanging precariously or a wall seemingly about to fall. The section had to decide what to clear first and the safest way of doing it. Front-end loaders proved invaluable for lifting large items – complete walls for example – onto the back of a truck. Having been loaded, trucks would dump debris at one of the many tips and then return to the work site where this process would be repeated. Anything from 5 to I0 truckloads were needed to clear the average house. [24]

In summary, the effort put in by the Armed Forces was tremendous. It was not only huge in quantifiable standards, but unstinting in its quality. It was carried on for months in 1975, long after the story of Tracy had faded from the newspaper front pages. In the end the Forces’ members were transferred back to their old, or in some cases new postings. For almost all of their time in Darwin they had been without leave.

Questions as to why there was no overall decoration awarded for this service were soon forthcoming. But there was no action taken, and therefore no group decoration made. There have been suggestions made to rectify this situation, but they have either met with silence or refusal due to various objections.[25] In many ways the lack of action can be summarised as follows:

- There is an expectation in the Armed Forces that unusual or arduous duty is part of the job. Indeed, rather than be paid an extra hourly rate or similar for work performed after normal 9-5 or weekday hours, ADF personnel are paid what was known then and is now as a “Service Allowance”. In 2023 that was $13,448 per year.[26] More money is paid to naval personnel who are at sea, and if deployed to a combat zone ADF members received additional pay, with income tax suspended for their time. So in many ways it is an expectation that Service life demands more. Then again, deployment to relief operations for Cyclone Tracy demanded much more: highly unpleasant work in extremely arduous conditions for week after week.

- There was no such honour as the National Emergency Medal at the time. However, there is nothing to stop the federal government making the decoration retrospective. Indeed, this has already been done: the Medal was established in 2011 but recognises operations from 2009.

- Many people argue that making such a medal retrospective would result in a flood of applications for it to be applied to other situations. To which must be said, what of it? Why not reward people for service beyond the norm? It can only serve to make such the Forces more attractive to both those who served then, and those who serve now.

- There would be difficulty finding the names of the personnel who served in Tracy operations. This is not a realistic argument. Considerable records exist from the time, and aircraft manifests and ship schemes of complement and the like are plentiful, as are pay records. Each branch of the ADF also contains personnel in historical sections who might well be tasked to find such records.

In conclusion, the award of the National Emergency Medal would seem both possible and have much to recommend it for Armed Forces personnel involved in Cyclone Tracy. There is sufficient time to bring this about before the 50th anniversary of the disaster at the end of 2024.

About the Author – Dr Tom Lewis OAM lived in Darwin for 25 years. He is a military historian, a best-selling author, and an on-screen presenter and scriptwriter. He is also a retired naval officer and the author of 21 books. His Order of Australia was bestowed on him for services to naval history. He has won numerous prizes for his literary works, the most recent being as the national winner of the 2021 Australian Naval Institute’s Commodore Sam Bateman Prize for Teddy Sheean VC. His book Cyclone Tracy and the Armed Forces will be released by Avonmore in December 2024.

[1] The Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. “National Emergency Medal”. https://www.gg.gov.au/australian-honours-and-awards/national-emergency-medal Accessed January 2023.

[2] Australian Government. Department of Science. Bureau of Meteorology. Report on Cyclone Tracy 1974. Australian Government Publishing Service, 1977. (p. 1)

[3] Department of Defence. The Defence Force in the Relief of Darwin after Cyclone Tracy. Australian Government Printing Service, 1980. (p.9)

[4] See the same author’s The Empire Strikes South, from Avonmore Books.

[5] Australian Government. Department of Science. Bureau of Meteorology. Report on Cyclone Tracy 1974. Australian Government Publishing Service, 1977. (p. 1)

[6] Australian Government. Department of Science. Bureau of Meteorology. Report on Cyclone Tracy 1974. Australian Government Publishing Service, 1977. (p. 2)

[7] Department of Housing and Construction. George R Walker. “Report on Cyclone “Tracy Effect on Buildings.” Department of Engineering. James Cook University of North Queensland, 1975.

https://www.jcu.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/1171341/Cyclone_Tracy_GRW_Report_1975_vol1.pdf (p. 7)

[8] Australian Government. Attorney-General’s Department Disasters Database. Australian Emergency Management Institute. 2012.

[9] Australian Government. Attorney-General’s Department Disasters Database. Australian Emergency Management Institute. 2012.

[10] Johnston, Eric Eugene. “Operation Navy Help: disaster operations by the Royal Australian Navy, post Cyclone Tracy.” Northern Territory Library Service, Darwin. 07 Jul. 1986 Web. 24 Feb. 2022. https://hdl.handle.net/10070/718204.

[11] Department of Defence. The Defence Force in the Relief of Darwin after Cyclone Tracy. Australian Government Printing Service, 1980. (p. 33)

[12] Hitchins, Air Commodore David. NT Archives. NTRS 226. (p. 75)

[13] Royal Australian Navy. Semaphore. Semaphore: Disaster Relief – Cyclone Tracy and Tasman Bridge. Issue 14, 2004.

[14] Royal Australian Navy. Semaphore. Semaphore: Disaster Relief – Cyclone Tracy and Tasman Bridge. Issue 14, 2004.

[15] Royal Australian Navy. Semaphore. Semaphore: Disaster Relief – Cyclone Tracy and Tasman Bridge. Issue 14, 2004.

[16] Digney, Larry. Bubbles, Booze, Bombs and Bastards, A Clearance Diver’s Story. Hobart: self-published, 2023.

[17] Royal Australian Navy. Semaphore. Semaphore: Disaster Relief – Cyclone Tracy and Tasman Bridge. Issue 14, 2004.

[18] Hitchins, Air Commodore David. NT Archives. NTRS 226. (p. 30)

[19] Royal Australian Navy. Semaphore. Semaphore: Disaster Relief – Cyclone Tracy and Tasman Bridge. Issue 14, 2004.

[20] Johnston, Eric Eugene. “Operation Navy Help: disaster operations by the Royal Australian Navy, post Cyclone Tracy”. Northern Territory Library Service, Darwin. 07 Jul. 1986. Web. 24 Feb. 2022. https://hdl.handle.net/10070/718204.

[21] Department of Defence. The Defence Force in the Relief of Darwin after Cyclone Tracy. Australian Government Printing Service, 1980. (p.56)

[22] Department of Defence. The Defence Force in the Relief of Darwin after Cyclone Tracy. Australian Government Printing Service, 1980. (p.56)

[23] Business Council of Australia. “Sir Peter Cosgrove interview on 3AW Mornings with Neil Mitchell”. 25 February 2020. https://www.bca.com.au/sir_peter_cosgrove_interview_on_3aw_mornings_with_neil_mitchell Accessed January 2021.

[24] Pedersen, Lieutenant PA. “A Platoon Commander’s Experience.” Army Journal. No. 316. September 1975.

[25] The author acknowledges letters and communication urging such action of Admiral Guy Griffiths AO DSO DSC RAN (Rtd.), and Captain Brian Swan AM RAN (Rtd.), which furnished me with information about the actions and processes here outlined.

[26] Australian Defence Force. “Pay & Entitlements.” https://app.defencejobs.gov.au/supporters-hub/parents/life-in-the-adf/pay-entitlements/ Accessed June 2022.

Contact MHHV Friend about this article.